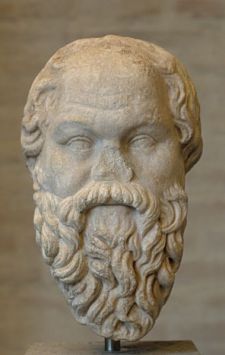

16 - Method Man: Plato's Socrates

Posted on

In this episode, the second of three devoted to Socrates, Peter Adamson of King’s College London discusses the way he is portrayed in the early dialogues of Plato, especially the “Apology.” Topics include Socratic ignorance and Socrates' claim that no one does wrong willingly.

Themes:

Further Reading

H.H. Benson (ed.),Essays on the Philosophy of Socrates (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992)

G. Vlastos (ed.), The Philosophy of Socrates: A Collection of Critical Essays (New York: Anchor, 1971)

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/socrates/

History of Philosophy's Greatest Hits: Peter discusses Socrates on video

Comments

Your comment at 5:56

When you postulated that Socrates was anything but apologetic, one can't help but assume you were being anachronistic. I mean no offense with that claim, and would like to see what you meant by that statement if you had meant to express something different, but Socrates was very much so being apologetic. That is, he was being apologetic in the sense of the Greek word apologia, which means to defend one's views in a formal setting, and which is the reason that Plato titled that work The Apology.

This word, apologia, is very popular amongst Christians who practice what is coined Apologetics, and these famous names happen to practice, or happen to have practiced, that academic pursuit: William Lane Craig, Gary Habermas, Ravi Zacharias, James Patrick Holding, Dee Dee Warren, Walter Ralston Martin (deceased founder of CRI, Christian Research Institute in Mesa, Arizona, that has a notable focus on refuting doctrinal claims made by alleged cults), and Hank Hanegraaf (current chairman of the board at CRI).

Here you can find a site devoted to Christian Apologetics, to peruse at your leisure some of the work done in this field: http://tektonics.org/ Navigate your way through the apologetics encyclopedia for their work.

In reply to Your comment at 5:56 by Luke Cash

Socrates the apologist

Right, I certainly didn't mean "apologetic" in the sense used for church debates, I meant it only in the more everyday sense (in modern English) of apologizing for what you've done. But you're right about the original Greek word: apologeomai means to speak in defense of oneself, and is in fact used often in legal contexts. In that sense Socrates is a paradigmatic case of someone who is being "apologetic" and of course that's the reason that this is the title of the dialogue.

What is Virtue?

Listening to Socrates quest to define virtue prompted me to try to come up with a definition (that he couldn't have brushed aside): Virtue is coupling power with responsibility.

Do you think he would've liked this definition?

~Adrien

In reply to What is Virtue? by Adrien

Defining virtue

That's certainly a better try than most of the interlocutors come up with! I think he'd probably test the definition in one of three ways: (a) he might say that the definition fails to be unified or general enough, but I think yours passes this test. Or, (a) he might give a counterexample, like a virtue that isn't satisfied by this definition; here I think you might be in trouble, because at least in Plato's dialogues things like "temperance" count as virtues; your definition looks more appropriate for "justice," say. Or (c) he might argue that the definition is too broad, so that there are some cases of "power with responsibility" that are not virtues (e.g. cases where someone has power and responsibility but not knowledge, and just gets the right result by luck).

If you could respond successfully to these points his next step, I guess, would be to ask for definitions of "power" and "responsibility"!

It's an interesting try though, do you think it would withstand these potential replies? (The ones in my first paragraph I mean.)

Peter

In reply to Defining virtue by Peter Adamson

Take Two

Power, in a broad sense, is a necessary condition for one's actions to be of any practical or academic significance; temperance can only be considered a virtue if practiced by the powerful. The [completely] powerless can be unvirtuous, but not virtuous. I guess what I'm coming back to is that virtue is the powerful being responsible. But probably "being responsible" is too generic.

Maybe a simpler (and in my mind more elegant) definition could exclude the notion of "Responsibility": Virtue is the powerful selflessly limiting their power. I think the 'selfless' qualification implies knowledge and intent.

But what is 'power'? How about this: Power is any ability to alter one's environment, which includes other agents. For example, an infant has power over her mother, since she can alter her behavior.

I think this definition passes test (c). For tests (a) and (b), I searched for examples of virtues on the Web and got the following: hard work, perseverance, honesty, integrity, compassion, generosity, courage.

I think 'honesty' and 'integrity' fit well under this definition. But the other examples are more interesting,

--Hard Work: I have the power to slack off or procrastinate, hard work is limiting that power

--Perseverance: I have the power to give up, perseverance is limiting that power

--Generosity: I have the power to hold on to my assets, generosity is limiting that power

--Courage: I have the power to be a coward, courage is limiting that power

I noticed two problems though: 1) In defining these 4 examples, I'm using 'power' in a way that doesn't quite fit the above definition. 2) Limiting my power to slack off or be a coward are not necessarily selfless.

So I'm rethinking my new definition. I'd appreciate your input.

~Adrien

In reply to Take Two by Adrien

Power and responsibility

Thanks, this is interesting.

I'm a bit worried that whether you add "with responsibility" or "selflessly," you might be in danger of giving a circular definition. (How is what you are saying different from: "virtue is the use of power, but only when used virtuously"? Meno falls prey to this problem too.) But leaving that aside, I am surprised that you define the various virtues in terms of the "power" to do something _wrong_, e.g. procrastinate, be a coward, etc. When I first read your definition I thought you meant that courage would be e.g. the ability (power) to fight in battle plus the sense of responsibility that makes the use of that power turn out as a virtue rather than as a vice. Maybe this is what you have in mind with your first worry at the end of the email. I agree with the second worry too, which is that it isn't clear that all virtues involve selflessness. In fact, Aristotle would probably want to say that _no_ virtue involves selflessness, since his account of virtue is that one seeks virtue in order to secure happiness and flourishing for oneself. That doesn't exclude the welfare of others, as is clear from his discussion of friendship, but I think for him virtue is never entirely selfless, and certainly it doesn't _need_ to be selfless.

Peter

In reply to What is Virtue? by Adrien

Virtue is Arete, Excellence

I can not believe what I read. "Virtue is coupling power with responsibility" is not at all what Virtue is. Not even coming close.

Before one does philosophy, one has to have some training in Classical Studies of Greek and Rome. You can not, and I emphasize again, you can NOT do or understand Greek philosophy unless one has a grounding in Greek classical studies. One has to read especially the books by Edith Hamilton.

What answers Adrien's question is Werner Jaeger's Paideia. Whole chapters are devoted to it and its historical connection.

Philosophy is tied to Virtue and without a clear understanding of Virtue, there is NO philosophy. No one, and I mean NO one should jump into philosophy without at least a good grounding in Greek culture first, and especially Doric Culture.

Virtue is the excellencies of a man's character.

I mean just a philological dissection of the word virtue tells you what it means! What are the first three letters of the word virtue? V-I-R. That is Latin for Man. Virtue literally means "To be a Man". Virtus in Latin. The Greek is Arete. It means "Excellence".

Virtues are excellencies of the character of anything.

In reply to Virtue is Arete, Excellence by W Lindsay Wheeler

Classical training

I have to respectfully disagree. I guess it's obvious, in a way, that I would disagree since I am putting a podcast on ancient philosophy out, without requiring people to go learn Greek and Latin before listening to it! Clearly one can never understand these texts at the highest, most detailed level without reading them in their original languages, but in my view anyone can get a lot out of Plato (and even Aristotle, though he is harder) just by picking up a translation and reading these wonderful texts. In fact this is how a lot of people, including me, got into classics or philosophy in the first place.

In reply to Classical training by Peter Adamson

Jaeger & Hamilton's works

First, I have to agree with Peter here: Of course knowledge of Greek (and Latin) helps immensely with studying the texts, but it is not a necessity that can't be helped. In fact, I'd say that reading a translation (or two) is quite sufficent for starters and oftentimes an indispensible tool for those able to read greek as well.

That said: Werner Jaeger's Paideia, though it is a great work in it's own right in my opinion, is highly idealizing the ancient greek education and downplaying non-greek influences on our culture, both in their scope and importance as well as their value. The same is true for Edith Hamiltons works. Their ideas of how the ancient greeks lived and how their education worked were not objective at all, but biased.

Also, there's logical reasons why one can't study Jaeger and Hamilton before studying (greek) philosophy: Both Jaeger and Hamilton's work are greatly influenced and one might say soaked by their own reflections on greek philosophy that studying them amounts to studying interpretations of and thus - at least indirectly - greek philosophy (intermingled with a good dose of German idealism and romanticism, I guess). Thus one would have to study Jaeger and Hamilton's books, before one were to study their books.

It seems impossible to me, though, to do x before doing x.

Regards,

Peter

In reply to What is Virtue? by Adrien

virtue

By far the best full definition of virtue to date. simplicity at its best.. Thank you

Irony

I'm currently reading "The Art of Living, Socratic Reflections from Plato to Foucault" by Alexander Nehamas. I'm only at chapter 3 but the whole thing appears to be about Platonic Irony. A subject I never heard of and never knew there were so many people who wrote about it! ;-)

Nehamas writes, "I cannot, for example, accept Norman Gulley's view that Socrates already knows what piety, courage, or temperance is but pretends he does not so that his interlocutors will endeavor to discover it for themselves." p72. Until I started reading this book, I hadn't thought about questioning Socrates' sincerity regarding his ignorance of these things. I then read one of the dialogues again and saw how you could read it this way. Earlier in his book, Nehamas makes the point that (not sure if this was his point or someone he quoted) how could Socrates not know these things when he himself lived a virtuous, courageous, and temperate life? Is the point of all this to show that you can't explain any of these things but only live them? Then it made me wonder if we should consider Socrates to be the first Zen monk! -- trying to show the futility of words when it comes to living a life as a philosopher. ;-)

In reply to Irony by clem

Socratic irony

Hi there -- Indeed this is one of the big issues discussed in secondary literature on Socrates. (With Nehemas you are reading one of the most significant contributions but the debate goes back at least as far as Gregory Vlastos.) My colleague at King's College, MM McCabe, was always very careful about throwing around the word "irony" when discussing him. It's too often a way of dismissing what he says as a joke, rather than thinking about it. Rarely or never is what he says "ironic" in the sense of "so sarcastic that even his interlocutor knows he is not being serious. So you often or always have to think about why the surface meaning of what he says would perhaps be plausible. I agree with you that the issue about how he can be virtuous relates to irony, I think, especially in that we need to decide whether he's being in some sense ironic when he says he is ignorant. This again seems to be to some degree serious: he lacks the "divine wisdom" he talks about in the Apology. But does it mean he has no knowledge of any kind? No reliable beliefs?

Thanks for posting!

Plato's esoteric writings?

Hi, Peter,

I'm just catching up with your podcast -- hope it's fine to comment on an entry almost one year after the fact!

I remember reading in Guthrie's history that Plato's dialogues might have been aimed at the lay person with an interest in philosophy, and that he might have had more systematic writings, for the exclusive use of academic philosophers. Is this idea discredited nowadays?

I'm enjoying your podcast a lot. Thanks for it.

Manolo

In reply to Plato's esoteric writings? by Manolo

Plato's secret doctrines

Hi Manolo,

Of course comments are always welcome, no matter how long ago the episodes went up!

I don't think anyone thinks that Plato wrote a bunch of esoteric texts which are lost. However there is considerable dispute over whether in conversation he may have shared positive theories -- sometimes called the "unwritten doctrines" -- with his students, which are not found in his dialogues. Some evidence for this is that Aristotle sometimes talks about Platonist doctrines that don't seem to appear in the dialogues, though some claim to be able to find them there (like Ken Sayre with whom I studied at Notre Dame, actually). The unwritten doctrine theory is especially associated with the "Tübingen school" of interpreters.

Anyway I think probably the mainstream of Plato scholars is nowadays happy to focus on the dialogues and not worry too much about the unwritten doctrines, if there were any. (After all the dialogues offer so much to think about on their own.) The idea of unwritten doctrines becomes more important in assessing Aristotle's critique of Plato and Plato's relationship with his immediate students, for which see episode 51.

Cheerio,

Peter

Socratic Ignorance

Would it be plausible to conclude that Plato indeed perceived Socrates in the way Xenophon did regarding his modesty and humility? Plato's perception seems to come off as criticism that the apologeomai of Socrates himself that he "knows nothing" suggests that although living a virtuous life it sets apart from being divinely wise. The end of his quest of virtue came by the experience of divine guidance. Isn't divine wisdom, discernment; knowledge of what is true/right coupled with guided judgment as to cause action -from a divine entity?

Therefore; divine wisdom and virtue can be found and attained only by divine guidance through experience.

In reply to Socratic Ignorance by D'Andre

Plato vs Xenophon

I think Plato, especially as his career goes on, becomes more dissatisfied with the Socratic stance than Xenophon ever is. Hence we see Plato going his own way and trying to develop methodologies that could bring us to philosophical insight (the method of hypothesis, collection and division). So I would see a difference between them on that score.

Dialogues

Are there "professional" philosophers currently writing dialogues?

It seems this writing method is more courageous than the usual euristuc but perhaps I'm wrong.

In reply to Dialogues by TD

Dialogues

I don't think it is a commonly used form, no, though I can think of at least one article on analytic metaphysics that was written as a dialogue (by Dean Zimmermann). Perhaps the things that drew Plato to the form are exactly the things that make philosophers nowadays shun it - the unclarity of the author's own position, the desire to explore various views without declaring one's allegiance to any one of them, the link to "literary" production? But then of course we are only guessing when we talk about Plato's reasons for writing dialogues.

In reply to Dialogues by TD

Dialogues

Among contemporary Analytic Philosophers, especially John Perry comes to mind: he published several dialogues (check bookfinder or amazon), two of which were translated into German (cf. Reclam). -- In Germany too, Ernst Tugendhat published a dialogue on ethics (cf. Suhrkamp).

In reply to Dialogues by TD

I'm currently reading a

I'm currently reading a dialogue by Cicero on friendship and old age -it's quite good- but it has revealed some strengths and weaknesses of this technique I missed when reading Plato's corpus. I guess the weakness of dialogue is the implied certainty on the issues by the main interlocutor. In the hands of a philosopher like Plato, who utilizes reason and established -directly or indirectly- first principles, the technique seems quite effective; whereas, in a sophist's hands it tends to beguile and "lead the witness" down irrational paths under a guise of rationality.

In reply to I'm currently reading a by TD

Dialogue

Yes, that's a nice point. Perhaps this is what Plato had in mind when (in the Sophist) he described what seems to be Socrates' method as a kind of "noble sophistry"?

Plato's disdain for the court and demos in general at 290?

"Though -speech making- after all there is nothing remarkable in this, since it is part of the enchanters' art and but slightly inferior to it. For the enchanters's art consists in charming vipers and spiders and scorpions and other wild things, and in curing disease, while the other art -speech writing- consists in charming and persuading the members of juries and assemblies and other sorts of crowds"

It's harder to charm snakes, spiders and scorpions than the demos, who may be human versions of snakes, spiders and scorpions?

Is this an alusion to how Socrates was biten with the poison of hemlock and laid low, perhaps proving even he lacked the power to enchant those minds of brutish disposition all because he wanted to cure them of their worse illness; ignorance.

Socrates and other are puzzled

Hello Peter,

I've been enjoying the podcast immensely. I was wondering about the typical trajectory of Socrates and his conversant ending their dialogues in a state of puzzlement. Could this be an effort on Plato's part to show that Socrates is NOT a sophist? After all, if the sophists are all about convincing others about any topic and Socrates can't convince anyone of anything, he must be a very different animal than those sophists.

What do those that spend time with the sophists, Socrates, and Plato think about the ending state?

Thanks,

James

In reply to Socrates and other are puzzled by James Conder

Puzzlement and the sophists

That's a nice idea, and it could well be that the Socratic approach is meant to distinguish him from sophists like Gorgias - to some extent this is even explicit, as when Socrates meets Gorgias (in the Gorgias) and insists on brief question and answer rather than long speeches. (Gorgias brags he can answer briefly and manages to respond to the first several questions with one word, "yes", at which point Socrates praises him for his concision!)

However it is more complicated than that because there were other sophists, like the brothers in the Euthydemus, whose arguments produced befuddlement. So if anything I think it is more likely that the aporia/puzzlement produced by Socrates would have been a reason to think he was indeed a sophist, but of the "eristic" rather than rhetorical variety.

the Socratic method

Hi Peter,

I am really enjoying your series of podcasts, and I have a couple of questions about the Socratic method.

I see that it could be a necessary step before the search for wisdom, but I'm wondering what exactly is achieved with the Socratic method. It seems to me that when the interlocutor finds himself in a state of confusion, his belief set has been shown to be inconsistent in some way. But it doesn't necessarily show which particular belief is the 'faulty' one, so it is not clear that Socrates gets rid of his interlocutor's false beliefs, which I take to be a necessary step to starting the real 'search for wisdom'?). I take it the false beliefs are the target, because surely to start the search for the meaning of 'piety' etc. would require some beliefs/intuitions, such that the Socratic method cannot aim to destroy all commitments to any particular beliefs?

Also, it seems that some of the dialogues, the interlocutors accept certain assertions (of Socrates) fairly uncritically - the Socratic method seems then to test the consistency of a particular interlocutor's belief set (for Socrates appeals to what the particular interlocutor accepts or does not accept), rather than the truth or falsity of their beliefs. For if an interlocutor came out of a Socratic dialogue unscathed, i.e. her beliefs were consistent, she wouldn't then necessarily know the truth about piety. Conversely, just because one interlocutor is unable to defend some thesis, it may not mean that thesis is false. Or is that precisely the point, and we need some better method for getting to the truth of things (once we realise we can't really defend the bits of knowledge we think we have) - but then, what of the positive search?

Thanks!

In reply to the Socratic method by KP

So-crates' Method

you might consider skipping (or waiting until you get to) to around episode 70. The point you highlight is an important one and one which provoked real ancient debate. For instance the early followers of Plato embraced the skepticism they saw in the Socratic Method and which you are picking up on (and indeed the early Academy would say you are on the right track with this thinking). If Peter doesn't respond know that this subject will get a lot of airtime later on in the series.

In reply to the Socratic method by KP

Socratic questioning

I used the Socratic method on my brother at the beach this holiday weekend and it frustrated him immensely. But he at least learned that what he thought he knew he actually didn't . He didn't like this much; however, he now has an appreciation for making sure he knows the subject very well before he makes comments on it. All should use this method especially since the world is a rational place and the answers are there if one is willing to push hard to find them, always remembering to put any answer through the Socratic mill grind.

In reply to the Socratic method by KP

Socratic inquiry

Thanks for this insightful question and the replies that have already been made. I think your analysis is dead on and in fact this problem has been pointed out by some secondary literature on Socrates: if he shows you that your previously held beliefs A, B and C are inconsistent, why should you then abandon A rather than B or C, as he wants you to do? Actually it would be open to the interlocutor to pick any of the beliefs to abandon, and in practice in the dialogues it usually seems dramatically and dialectically unproblematic that the characters settle on the culprit belief that should be rejected. But nothing actually requires this apart from the preferences/intuitions of the characters involved (essentially they discover that their commitment to A, while previously strong, was not as strong as their commitment to B and C).

I also think you are right that Plato himself was dissatisfied with the Socratic inquiry method, for the reasons you mention (and maybe others too). Most interpreters, I think, would say that the methods of hypothesis in the Meno and Republic and collection and division in the Sophist etc., are attempts to move past the method Socrates was suggesting. And I do get into these in the future episodes, as well as returning to the topic in the Skepticism episodes as has helpfully been pointed out!

In reply to Socratic inquiry by Peter Adamson

Socratic method continued......

The Socratic method has taught me to pick A as a starting point and follow it until it is proven true or until it is proven irrational, if irrational I move to B and do the same, if B is irrational than I move to C, if C is irrational I moe on to another option - this clearly exemplified in the Theatetus. The time limits within a dialogue force Plato to force Socrates to make some specious moves but this isn't the case in real life, we have far more time to investigate each situation, to me the dialogues and their short comings are only templates Plato outlines for our benefit and use in an expanded sense in the real world. Good scientists do this everyday, perhaps the reason why Plato said no one gets to rule as a philosopher king until they are experts in math, geometry, music and astronomy where you see the rational Itself. So I, myself still think the Socratic method trumps all other kinds of inquiry.

In reply to Socratic method continued...... by TD

Irrationality

But the problem is, what does it mean to say that a single belief is "rational"? Presumably that it is internally coherent (e.g. you shouldn't believe that cats are not cats). But beyond that you are presumably testing it for consistency with other things you believe, or (on a stronger, foundationalist epistemology) testing it to see if it can be inferred from some first principle. Plato seems to explore both options: the Socratic method is apparently an attempt to test for consistency, but as has been pointed out, discovering an inconsistency doesn't tell you what belief to discard; and also, even if your beliefs are consistent does that guarantee that they are true, or even rational? The method of hypothesis, especially in the Republic, then looks like an attempt to explore the foundationalist option.

The Theaetetus is, I agree, closer to the Socratic model, although it focuses perhaps more than the earlier Socratic dialogues on seeing what other beliefs are implied by or hang together with a given belief (e.g. that knowledge is perception). It seems to be an exercise in showing you what you might be committed to, if you adopt a certain belief. I quite like that actually, since I think that is what philosophy does best - discover how beliefs and commitments hang together in often surprising ways.

In reply to Irrationality by Peter Adamson

Irrationality and the Absolute

Indeed. Often the irrational is perceived and is disguised as rational. But perhaps the first thing one must do is ask themselves if they believe in a rational world based on absolutes and an absolute first principle. Until they come to terms with this I can't see how anyone might progress in seeing "Knowledge Itself". Surely there must be one single first principle undergirding all we think and perceive and perhaps had the Theatetus continued they might have come across this first principle -it seemed it was alluded to earlier in that dialogue and in other dialogues if I recall. But I could be all wet here -I have been in the past and will be in the future due to my predilection for the irrational in the guise of the rational.

In reply to Irrationality and the Absolute by TD

Absolutes?

Thanks for all the responses - I'll check out the above-mentioned dialogues and wait until I get further into the podcasts!

TD - I think my issue is even if we come to terms with, or admit as a possibility, a rational world based on absolutes and an absolute first principle, it is still not clear that the Socratic inquiry method we've been discussing would lead us there. Let's say the method could lead us to a first principle or a set of foundational beliefs or something, such that seeing what the consequences of our beliefs are, and discarding those that contradict perhaps our more firmly held beliefs leaves us with a set of absolute first principles/foundational beliefs. It seems then that we must have already always known the truth, and getting to it is just a matter of clarifying our beliefs, which is I guess what prompts the stuff about recollection in the Meno, to fill that explanatory gap about how we kind of 'know' the truth already in the first place, or how we can access it through clarification of our beliefs. So if we're talking about absolutes, then I'm not sure the method really works without an explanation of how we are already 'endowed with the truth' (although we may need a Socrates to help us work it out). The theory of recollection is one explanation but it seems a little ad hoc and implausible to me. But if we're not talking about absolutes, and knowledge/truth is reducible to a coherent/consistent set of beliefs, then I can see how the Socratic method might be useful for the pursuit of knowledge/truth. Though I'm not sure if this is a satisfying notion of knowledge/truth to have, because of the reasons outlined above.

I hope that makes sense...

In reply to Absolutes? by KP

The possibility of knowledge

I agree that the recollection theory looks like it is indeed intended to make us more optimistic about the prospects of Socratic (or any) inquiry succeeding. One thing to bear in mind here is that the kind of general skepticism lurking behind the question about whether there is any such thing as a rationally comprehensible "absolute" is really not on the radar for Plato and Aristotle. They seem to assume that knowledge is possible and happens, and be interested in explaining HOW it happens. In fact even the ancient skeptics aren't getting into the issue of whether the mind can represent some kind of mind-independent reality (an "absolute"). That whole problem seems rather to be something that emerges from later medieval and early modern philosophy. In one of the episodes just coming up I describe how it also emerged independently in Islamic India in the 17th century!

In reply to The possibility of knowledge by Peter Adamson

I have digressed

Sorry about the digression. At this point things can get off track and not pertain to the dialogue especially when the absolute comes in. Perhaps we leave it here and stick with comments related to the Socratic method.

Ugggghh....Worse than I thought

"The modern philosopher is a professional pedant, paid to instruct the young in philosophical doctrines and to write books and articles. He is a professor of philosophy, not so very different from a professor of biology or of marketing. He need not reshape his inner being to the model of the doctrines he discusses in his classes. If pressed, he will perhaps claim that he is useful because he teaches the young to think more clearly and, less plausibly, that he forces his fellow professors in other departments to clarify their concepts. The proud cities of metaphysics were long ago abandoned as indefensible and have fallen into ruin. The philosophers have for the most part retreated to the safer territory of language and logic, creating for themselves a sort of analytical Formosa."

John Walbridge. The Leaven of the Ancients:

Suhrawardi and the Heritage of the Greeks

In reply to Ugggghh....Worse than I thought by Duwain Hans Powell

Professional pedantry

Just out of curiosity, do you mean this as a criticism or the podcast or are you just agreeing with Walbridge about the state of contemporary philosophical practice? If the former, I think it is an unfair accusation since I talk very extensively about philosophy as a way of life etc in many episodes, I guess especially in the Hellenistic ones, but also for instance in the early episodes on India.

If the latter, then the criticism of course is a common one and in some sense is clearly right. On the other hand I think that even if philosophy can be, and has often been, devoted to the question of "how to live" it is reductive to think that philosophy is nothing but that. If you take a standard philosophical issue like "when can I take myself to have knowledge" or "do I have free will" it is obvious - and was obvious already in antiquity (read the Theaetetus or the Stoics) - that these are very difficult questions and any halfway decent attempt to answer them needs to get rather technical and precise. A common reaction to analytic philosophy and some parts of the history of philosophy (e.g. the scholastics) is that it is all time-wasting and technical navel-gazing. But the fact that it is difficult and technical may rather be a sign of the difficulty of the topics being considered.

Contradiction

After carefully listening to the Socrates podcasts a couple of times, there seems to me to be some kind of contradiction in what Socrates is doing/refuting his interlocutors and what he is doing himself.

On the one hand, as you mention, he is concerned that most people are right sometimes, which implies they are also wrong some other times. Therefor, he says, they don't have "true" knowledge about virtue, because they can't come to a general defintion which is always right. He doesn't claim he himself has the true definition, but he claims he can learn as much as possible and - who knows - maybe find the ultimate answer by asking questions.

On the other hand - and I hope I can make myself clear on this as a non-native English speaker - the right/wrong principle also works one level higher up. One man can sometimes be right and sometimes be wrong, and Socrates can then jump to a conclusion about what virtue certainly is (or most of the times: is not), but another man maybe right or wrong about other things (or even the same things), which might lead the same Socrates to a different conclusion. As much as you have rights and wrongs in one person, you have more general rights and wrongs over multiple people, so if it Socrates claims one man can't come to a definite answer about what virtue is, why would many men?

Which leads me to think: is Socrates really trying to get a true definition of virtue, or is he fully aware that he won't get it from the people of Athens and is he just showing them they are all wrong sometimes? If you're the smartest man in town, this seems a bit... lame, no? Somewhere in between the lines, he seems to say: there is no absolute truth, but I'll pretend there is one by pointing you all to the errors in your thinking. Money, goals and methods put aside, purely based on believes: doesn't that make him kind of a sophist? :-)

In reply to Contradiction by Senne

Socrates

Thanks for the comment! I would say that it is clear in the dialogues that Socrates (as opposed to, say, Protagoras) assumes that virtue is the same for everyone. He never makes a move like "ok sure, that's what virtue is for you, but what is it for me, or some other person?" He rather gives counterexamples and objections to attempts to define virtue generally (classic example: to the definition "justice is returning what is owed" he points out that it wouldn't be just to return a weapon to a crazy person). In fact he sometimes rejects definitions on the grounds that the attempted definition is not general enough (as with Meno for instance, at one point).

However you are right that he has second-order beliefs of a different kind, for example that virtue is indeed the same for everyone, that it has something to do with knowledge, that it is beneficial. In fact he seems to have a lot of views about what virtue is like, just not knowledge of what it is. This doesn't make him a sophist, though: he is trying to get help to turn his incomplete grasp of knowledge (which is perhaps merely true belief) into a full and certain grasp, which would help him know for sure what to do in any situation.

Does that help?

In reply to Socrates by Peter Adamson

No, of course you're right, I

No, of course you're right, I admit my claim was too strong, it doesn't make him a sophist. (In fact I just listened to your 2 first unloved platonic dialogues in which you explicitly state this as one of Plato's "goals" of the Euthydemus: to show that "Socrates is no sophist!". Oops...).

But I was trying to understand why "common" people those days thought he was "kind of" like the sophists: here comes a man, probably the smartest man in town, who claims virtue is the same for everyone, but he can't really define it and so instead he questions others and puts their believes to the test. Of course this may teach Socrates some things and help him to get a fuller grasp, but in the two dialogues so far and in part of the Republic I've already read I find it hard to believe that Socrates is really trying to get to this certain grasp. He (or Plato for that matter) often seems interested or focused on pointing out false or wrong assumptions in ones believe set and if one nearly gets somewhere were things get to a certain point ("temperance is selfknowledge") he diverts the subject to something else ("what is selfknowledge"). While this is of course also worth looking into, how does it help the poor interlocutor (I mean Kritias the not-al-too-poor-tiran) to get closer to the truth (what should Kritias do? Stop thinking that temperance is selfknowledge? Why?) and how does it help Socrates? If Kritias would've been able to answer what selfknowledge is, would Socrates have said: "ok then, in that case temperance is selfknowledge?" I sincerely doubt it, he probably would've asked one more question. As you point out in some previous comments: he seems to keep testing his subjects for consistency about their ideas, which perplexes them the same way the sophists did, but this method doesn't seem to increase his nor his interlocutor's ability to know for sure what to do in any situation, on the contrary. To put it metaphorically, he sometimes seems like painter with an endlessly large, borderless canvas who hopes that with only more paint it will be finished one day. Seems impossible.

In reply to No, of course you're right, I by Senne

Socrates the sophist

I agree those are reasonable worries. Something that might help is to consider the fact that the dialogues are not transcripts of real conversations. The intended audience of the Socratic refutation isn't the (fictionalized) person he is talking to but the reader of the dialogue (i.e. you and me). So for instance your questions about what Critias should be doing in response is, perhaps, exactly what you are supposed to be thinking about, and the frustration and defeat of the interlocutor in the dialogue shows you as a reader where you'll wind up if you make the same wrong turns. Plato is also often trying to get us to see higher level questions about what it would mean to have real knowledge, of virtue or anything else; so part of the problem the interlocutors are having is that they don't know what kind of answer would be a good one. So in other words, I would say that even in the early "Socratic" dialogues Plato was exploring, and trying to get us to explore, positive ideas about virtue and knowledge indirectly by depicting failed investigations so that we can think about what went wrong.

In reply to Socrates the sophist by Peter Adamson

Thanks once again for your

Thanks once again for your time and insights, that’s a helpful way of looking at it. I was forcing myself too much to try and interpret the dialogues as “real” accounts of what had happened, faithfully representing Socrates and his interlocutors. Viewing them more as “explorations” and inquiries of Plato in which the reader also has to play an active part is a better way to look at it I guess.

Thanks for the beautiful series, really enjoying it!

Socrates and divine help

What was the point of anything if Socrates had "divine" help to begin with?

In reply to Socrates and divine help by Background

Divine help

His divine sign only occasionally warned him against certain ill-omened actions, it didn't give him knowledge of how to live which is what he was really after.

Socrates' Divine Sign vs Christian Revelation

Dear Peter,

(Apologies for using first names so readily, but using surnames seems to be so wooden, when I feel I know you enough, having listened to several of your podcasts, at least until this episode)

First of all, thank you for such an informative and entertaining project. I am in awe at seeing you have kept it going for so long. It has only come to my attention recently, thanks to a mention in a Prospects’ article on most influential thinkers in 2021 ( I voted for you incidentally). I am indeed coming to it very late, both in the fact that it has been running for ten years, so, like Achilles and the tortoise, I have a lot of catching up to do, but also in terms of age, I am 68, and so should have embarked on a systematic study of philosophy a long time ago rather than forage the verges as I had done so far.

Enough waffle, my question related to this episode is this:

How does Socrates’ divine sign or voice equate with the Christian notion of Revelation which implies we need a gentle, or not so gentle, divine nudge to gain an understanding of God/Virtue? Apologies if you are addressing this at later podcasts, and if so, please direct me to the relevant episode to save your time.

Kamal Bishai

In reply to Socrates' Divine Sign vs Christian Revelation by Kamal Bishai

Divine sign

Thanks for voting for me! And glad to hear you like the podcast.

That's an interesting question. One obvious point would be that Socrates' daimon did not reveal anything to him, for the most part - exceptionally he is advised to write poetry when awaiting his execution. But apart from that it only warns him away from things, so it has a negative function and thus does not really impart knowledge or information, as revelation does in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. Also I don't think there is any sense in Plato that there are things we can only know through divine revelation. If anything, the gods speak in riddles or send signs that require independent inquiry to understand, e.g. Socrates being told he is the wisest person in Athens. So this would be more like a spur to figure something out for yourself, than knowledge which would otherwise have been unavailable.

True Belief in Knowledge

I just find true beliefs in knowledge contradictory and controversial sometimes. I find it contradicting because one can have knowledge based on something they think is true, but to someone else they might have another answer or belief that is true to them. The other person's belief can still be based on reason but the answer or what they think is different as the other person. The person may find the other person wrong and vice versa.

Add new comment