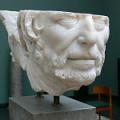

66 - You Can Chain My Leg: Epictetus

The greatest of the Roman Stoics is Epictetus, arguably the first thinker to discuss the nature of human will, and author of some of the most powerful and demanding ethical writings in history.

Themes:

A good translation of Epictetus is C. Gill and R. Hard (eds), The Discourses and Handbook of Epictetus (London: 1995).

• A. Dihle, The Theory of the Will in Classical Antiquity (Berkeley: 1982).

• C. Kahn, “Discovering the Will: from Aristotle to Augustine,” in J.M. Dillon and A.A. Long (eds), The Question of Eclecticism (Berkeley: 1988), 234-59.

• A.A. Long, Epictetus: a Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life (Oxford: 2002).

• T. Scaltsas and A.S. Mason (eds), The Philosophy of Epictetus (Oxford: 2007).

• W.O. Stephens, “Epictetus on How the Stoic Sage Loves,” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 14 (1996), 193–210.

Comments

Plotinus

Dear Peter

Just discovered your very interesting series and wondered since I am doing a PhD in Late Antique Paganism when you expected to start touching on Plotinus and his followers.

Thanks

Jill

In reply to Plotinus by Jill

Plotinus

Hi Jill,

Plotinus will be starting in episode 88 and I plan to devote 4 episodes to him including an interview. But if you like him you will probably also like the episodes on "middle Platonism" which will be numbers 78-81.

Between now and then there will be a couple more on Roman Stoics, then ancient skepticism, medicine and philosophy, and a general introduction to philosophy in the Roman empire.

Thanks for listening!

Peter

In reply to Plotinus by Peter Adamson

Hi Peter I will look forward

Hi Peter

I will look forward to Plotinus et al of his ilk and also the Middle Platonists!

Thanks

Jill

Free will for Epictetis

Hey,

As the local Unreconstructed Incompatibilist, I have to ask if Epictetus agreed with the classic Stoic position about all decisions being predetermined and unchangeable? If so, was he not aware of a hint of irony, in making our ability to chose the highest good? I pricked up my ears when you described the character who realised that the whole of his life up to then did NOT determine his next move - but then that was Satre, not Epictetus.

I also have a question about this idea of most-everything - like health and wealth and beauty - having "no value" in themselves. I gather, for the Stoics, what this actually means is: "The wise man trains himself to hold these things as valueless, so that he will not be disturbed if he loses them". Is that right? Bc, if so, I don't see why the wise man should not, instead, train himself to appreciate the value of such things, while also holding himself ready to live without them. I mean, it's good to have a nourishing meal today, even if (especially if?) you're likely to go hungry tomorrow.

I wondered if the "all things are valueless" axiom maybe had some resemblance to the Buddhist idea of all things being illusions? Not that I'm thinking the Stoics were aware of the Buddhists (I'm not even sure of the relative chronology). But I wondered if the central insistence on things being valueless, has to do with some understanding of the physical universe as not-as-real as the psychic universe (if you understand what I mean).

Marissa

In reply to Free will for Epictetis by Marissa

Freedom again, and value

Hi Marissa,

The question about Epictetus is a difficult and much-discussed one. Basically he doesn't get into any discussion about whether our will (prohairesis) is causally determined by god, but the usual assumption is that he would have followed previous Stoics and their compatibilist line, given that he does talk about god's providentially bringing about all things.

Your point about the Stoics and value is a good one, but maybe the Stoics have already made the move you want them to. I think what you're suggesting is that we could value something without saying that our happiness depends on it -- thus I appreciate them while being ready to lose them, as you say. But that's just what the Stoics mean by a "preferred indifferent," I would say. The "preferred" part indicates that there is some sort of value here. (This is what was being discussed on the blog regarding G. Karamanolis' paper, here.) The question is whether they can tell a coherent story about what that lesser kind of value is; one thing I'm sure they would say is that this value depends on circumstances, e.g. health is preferred all else being equal, but sometimes all else is not equal and I might give up my health to do something virtuous. By contrast virtue is valuable "in itself" in the sense that its value is indefeasible.

Thanks!

Peter

Chronology of Buddhism with Stoicism

Coming in very late here. Marissa suggested a Buddhist link in denying that she intended one, but it's not absurd. Indian Buddhist king Ashoka the Great (304-232 BCE) is said to have sent missionaries to the West, well into the Greek speaking world in the generation before Zeno. I'm not up on the scholarship, but chronology alone doesn't exclude the possibility that exposure to Buddhist ideas was prevalent in the philosophical world of the early Stoics.

Your thoughts on that, Peter?

In reply to Chronology of Buddhism with Stoicism by urban

Buddhism and Stoicism

Better late than never! To be honest my knowledge of Buddhism is minimal enough that I would be cautious about expressing a strong view on this. But for what it's worth:

(a) The scholarship I have read on connections between Indian and ancient Greek philosophy has never persuaded me that there is good evidence for historical influence (I'm more familiar with attempts to show it for Neoplatonism, which is of course later so in theory even more possible). Rather what you tend to get is impressionistic observations of intellectual parallels which don't really hold up once you get into the details. A lot of people would quite like there to be influence of Indian thought on Greek philosophy -- it would be exciting after all -- so the fact that no one as far as I know has turned up really good evidence strikes me as significant.

(b) Early Stoicism makes an awful lot of sense as a response to its immediate Greek context, especially as a reaction against atomism and engagement with Plato's Timaeus. So I'm not sure there is much for additional influence from Buddhism to explain. Furthermore I think the really striking parallels are probably more to Roman Stoicism which comes later, but again Roman Stoicism seems to grow organically out of the Hellenistic tradition, as I explained in these episodes.

Thus, while admitting my lack of expertise regarding the Indian tradition I would be cautiously skeptical, but I would be totally open to being convinced otherwise. I actually hope someday to circle back in these podcasts to Indian and maybe Chinese philosophy, so maybe I can revisit the question with more information in my brain, if and when I manage to do that. So far I have been discouraged from doing this by the desire to press on to my main area which is medieval Islamic philosophy, plus my almost total ignorance which makes it seem rather daunting!

Cheerio,

Peter

In reply to Buddhism and Stoicism by Peter Adamson

When you might do Eastern philosophy

Given the relevance of this reply to my question on the general comments board, I'm happy to have read it. So is the idea that you might finish off the tripartite medieval section and then go back at that point to the ancient world for Indian and Chinese philosophy?

Sinn-des-Lebens-business

Hi Peter,

your're the best to ask about this on behalf of our students (if I may):

Coming from a seminar where we discussed with them Tom Nagel's essay ‘The Absurd’ from his Mortal Questions, as well as the final chapter of his View from Nowhere on ‘The Meaning of Life’ etc., I wondered what classical and/or medieval sources there might have been for all this "Sinn des Lebens" business. What would come to mind, as far as you're concerned? (& which postcasts might we perhaps re-listen to? probably Hellenistic ones?)

This murky + curious topic is of course seldom taken up in contemporary analytical philosophy, though Moritz Schlick comes to my mind as one who has written about it, and there are remarks by Wittgenstein. And of course there are all those existentialists, foremost Camus (who inspired Nagel).

So what would come to your mind, from among the philosophers you have discussed so far or from later periods?

All the best for your new start into the Western medieval tradition,

Michael

In reply to Sinn-des-Lebens-business by Michael Gebauer

Sinn des Lebens

Hi Michael,

Well, you've put your comment on the right page since Epictetus is among the most important ancient thinkers for this question. In general I'd say that the usual story that ancient philosophy was more focused on "how to live" than current philosophy, is that rare thing: a cliche that is pretty much true. So if you revisit the episodes and sources on Hellenistic ethics that would definitely speak to the issue. Also, I would highlight the Christian ascetic movement as a major contribution here, and one that is still indirectly very influential today.

What we don't find until relatively recently, I would say, is the worry that life might in fact have no meaning at all - that we are just here by chance or whatever. (Even the Epicureans, who did think everything was the result of chance, didn't get anxious about this, or indeed about anything else.) For that you probably need the rise of modern physics.

Thanks,

Peter

In reply to Sinn des Lebens by Peter Adamson

Sinn-business

Thanks, Peter

that sounds re-assuring, and we'll surely have many a second & third (etc.) look (& listening) in the areas you mentioned. -- After all, it'll take a while until you get to our notorious latter-day existentialists. -- So let's recommend Epictetus first to our students, as well as your earlier podcasts, of course. Maybe you'll come up with some unexpected others in the future.

Cheers,

Michael

It's all Greek to me

Hello Peter

My normal approach to philosophy is to take what I might find helpful for myself, what might be interesting to talk about and to amend anything that might be useful to me, by tweaking it a little to suit myself. It's not really a scholarly approach. However, I've become interested in Epictetus and would like to know what he actually said. Epictetus seems to believe in an afterlife. He talks about death as being the mere separation of your soul from your paltry body. It's harder to be his kind of Stoic if you don't believe in an afterlife. He also seems to put a lot of weight on "bad" things happening to you as a part of God's great plan. Something you can't understand. If you don't believe in God, or a great plan, it's harder to take comfort from that kind of Stoicism. Then there's the ambiguous business of what living in accord with nature is supposed to mean.

I'd like to take a scholarly approach to this, so would normally go back to the original text. The problem is I don't speak Greek. I've read parts of different online translations and got the Discourses from the library, but they are strikingly different. I'm not sure if some have a Christian agenda and have added in extra God, or if some have a secular agenda and have taken out superfluous God. What would be your take on getting to what someone actually said, where you don't speak their language?

With Epictetus of course, even if I spoke Greek, the Discourses would still not be the direct words of Epictetus, because they were written out by Arrian, who may have worked in his own concerns and interests, either intentionally or unintentionally.

Incidentally, the Discourses I got from the library were published in 1927. The first page had about thirty or so date stamps printed on it from people who had taken the book out over the years. Epictetus was a part lame, ex-slave who lived 2000 odd years ago, but people like me, were still interested in what he had to say all these years later. I felt a connection to those date stamps and it was a nice feeling.

Love the podcast!

In reply to It's all Greek to me by Wannabe Scholar

Greekless reading

Thanks, glad you like the podcast. Of course this is a big problem and one I have been facing myself now that I am looking at Indian philosophy (I don't have Sanskrit or the other relevant languages, but at least I can depend on Jonardon who does). The main thing I would say is that you are already on the right track by worrying about it, rather than taking the translation at face value. It can also be a good idea to compare multiple translations, if there are more than one which is true with Epictetus.

Regarding your specific question on him, the Stoics would believe in an afterlife at least in the sense of the soul rejoining god (since our souls are part of the fiery divine substance). But actually I don't think Epictetus does need to insist on an afterlife: for him and for all Stoics, happiness lies solely in virtue and, in the unlikely event anyone could manage to live virtuously, they would be happy whether or not they continued to live on after death. His idea is that you should only value what is within your power, i.e. your choice, and I don't see why postmortem survival would be necessary within an ethics built around that conception of the good life.

In reply to Greekless reading by Peter Adamson

Thanks for the reply

My understanding more or less overlapped with what you wrote, so pleasingly it appears I've grasped the fundamentals.

I agree that for the Stoics virtue is all and that they don't need to insist on God or an afterlife. With God and an afterlife though, the Stoic message is much easier for Epictetus to accept and embrace, whereas if someone doesn't believe in God or an afterlife, the message is much starker.

Take the case of someone lives in a time of civil war, gets cancer and watches their children die from famine. The Stoic message is easier to swallow if they can comfort themselves with their suffering being part of God's greater plan and that when they die, they will move on to something better. Much of the appeal of religion seems to be the imposition of purpose on the universe and the promise of a better life after this one. Without God and an afterlife, there is no purpose to our suffering, it's random, it's senseless, it has no reason, and on top of that, this life of suffering is all we get, there is nothing better to follow after we die.

The underlying message is the same, to live a good life, virtue within your choice is all you need, and I'm sympathetic to that. However, the version of Stoicism that wraps that up in the understanding that your suffering makes sense in the bigger picture and also has the promise of something better to follow, seems to be softer and more appealing. At least to someone who is not already a sage. So I wonder how important God and an afterlife were to Epictetus and whether he would say the same blunt things, in the same blunt way, if he didn't believe in God and an afterlife. I'd also like to satisfy myself about what he actually said, but as learning Greek is probably beyond me, I'll have to accept that as an open question.

There are many good podcasts out there, too many to listen to, yours is one of the best.

In reply to Thanks for the reply by Reading the Di…

bored

Offhand somewhat boring, to say the very least -- WHAT THE HECK IS [or was} "VIRTUE"? -- perhaps, we'll get to hear more on it when discussing its medieval fans. -- Nut I myself am not sure if I grasp what you are even trying to talk about, if I'm being serious. -- Anyway, I guess this problem will remain with me (+ you fols), so sorry, M.

Slavery

It's odd that Epictetus doesn't explicitly oppose slavery. Despite having been a slave himself, he appears to accept it as an inevitable institution in society. He writes a lot about slavery, but mostly as a metaphor. In his Stoicism, a chained slave can be free if their will is free, whereas a free person can be enslaved if their will is attached to desires outside their control.

That which is not good for the swarm, neither is it good for the bee. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 6:54

Marcus Aurelius talks about the need for everyone to play their role and to act in the best interests of society, role playing bees for the good of the beehive, living in harmony with nature. Yet, he was emperor for two decades and made only small changes to improve the lot of slaves. He could be criticised for not doing more and he could be credited for doing more than nothing. But, he had the power to substantially challenge slavery and didnt. As he didn't do more, it looks like Aurelius thought that being a slave was some people's purpose in life. As I see it, it doesn't speak well for Aurelius' Stoicism, if it's compatible with institutionalised slavery.

So, the Stoics talk about playing the role you have been ordained by providence as best you can, but I wonder how that applies to Spartacus? Was Spartacus' role to be an obedient slave, serving the social world of Rome? Or was Spartacus' role to be a rebelious slave, leading a slave revolt, tearing up the social world of Rome? How would Spartacus know what providence had ordained was his purpose in life? The Stoics not very helpful answer is to be virtuous. But one man's terrorist is another's freedom fighter, so to me, what is virtuous for Spartacus collapses into a kind of subjectivism ultimately. As I lean that way, I don't find that problematic, but many would. If it's not subjective, the Stoics should explicitly spell out what is virtuous. The four Stoic virtues are wisdom, courage, justice and temperance, but with a little work and imagination, all of those seem compatible with both being an obedient slave and a rebelious slave. Even if people translate the original Greek as excellent and not virtuous, it doesn't seem to help. Subjectivism or not, the Stoics can be read as saying accept your slavery and be the best slave that you can be.

If a modern Stoic thinks Spartacus right to revolt, it seems they should also think Aurelius wrong not to make more of a substantial challenge to slavery, even if it shook up Rome itself, which is what Spartacus did. If Aurelius believes his Stoicism has social concerns, it looks like he fails to live up to his own philosophy. His public action doesn't match his private preaching. Perhaps Aurelius thought the bees were freeborn Romans and that the beehive was Rome. Everyone else was just an "other" not worthy of moral consideration. That seems to be how black people were enslaved in the Americas and how the Jews were gassed in WW2. Blacks and Jews were "other", "them" and not "us". Perhaps Aurelius' private writings were just private rationalisations. Or perhaps the weight of society was too much for him to shift, even if he had wanted to. Other Roman emperors had the will to turn the empire to Christianity, so I'm skeptical that Aurelius was powerless.

In a round about way I wanted to ask about Epictetus and slavery. We know Epictetus through Arrian, who was well-to-do and may have owned slaves himself. Perhaps Arrian didn't write down Epictetus' views on slavery. Perhaps Epictetus didn't express them to his wealthy clientele. Perhaps Arrian wrote about them in the missing books.

So, given your background knowledge of the time, how likely is it that Epictetus would have accepted slavery? Were there other thinkers who were loudly rejecting slavery? Would there have been near universal acceptance of it? In a similar way to how there is near universal acceptance today, of something like nation states or prisons. Slavery seems to me the kind of thing a philosopher should question. What prompted me to post was reading Aristotle's pro-slavery passages in Politics and in his favour he did question slavery, albeit coming to a different conclusion than the current prevalent view.

Much of what Epictetus says suggests that he would be against slavery, but that's never made explicit and the same might be said about Aurelius. I wonder how likely you think it is that Epictetus would accept slavery, or endorse it, or simply think it an irrelevance, an indifferent in Stoic terms, because physically enslaved people can still lead virtuous lives?

In reply to Slavery by Manumission

Stoics and slavery

This is a great question. In fact I decided to talk about this in the book version of the podcasts on Hellenistic philosophy - there is an added chapter in vol.2 of the series, which talks about ancient ideas of the household and it includes a bit about slavery and in particular what the Stoics say about it. So, you can check that out, but just in brief I think you are right to suspect that their treatment of the topic is rather disappointing. While I don't think they would counsel a slave to be "the best slave they can be" they tend to think of slavery as a condition like poverty or illness: not rationally to be preferred, but as you say, ultimately "indifferent" i.e. irrelevant to one's happiness. They certainly never argue for abolishing slavery, though they might suggest that slaves should be treated well, and the general line seems to be that a slave should accept their lot in life the way we all have to accept whatever providence dishes out to us. The good news is that for the same reasons the slave can be virtuous, just as the prisoner can (Epictetus: "you can chain my leg but not my will").

In reply to Stoics and slavery by Peter Adamson

Slavery

I have a lot of thoughts about Stoicism and slavery, having been thinking about it recently, but will try to be as short as I can. Not very ;)

Moral realists will often give the example of slavery as something that's so obviously wrong and repugnant, that moral realism must be true. I always think that it wasn't so obvious to people two thousand years ago and it's not even so obvious today, as there are probably more slaves alive in the world now, than at any other time in history.

If I had a favourite philosopher, it would be Epictetus. It pains me somewhat that you think he wouldn't object to slavery as an institution. I've come across a lot of modern Stoics who insist that Stoicism is politically engaged and concerned with social justice. That seems like wishful thinking to me, especially where slavery is concerned.

I will push back a little, with respect, against your view that the Stoics would not counsel a slave to be "the best slave that they can be". That is what Epictetus seems to say here:

"We are like actors in a play. The divine will has assigned us our roles in life without consulting us. Some of us will act in a short drama, others in a long one. We might be assigned the part of a poor person, a cripple, a distinguished celebrity or public leader, or an ordinary citizen. Although we can’t control which roles are assigned to us, it must be our business to act our given role as best as we possibly can and to refrain from complaining about it. Wherever you find yourself and in whatever circumstances, give an impeccable performance. If you are supposed to be a reader, read; if you are supposed to be a writer, write." Enchiridion 17

I'm probably being hard on Aurelius. If I had been emperor, I wouldn't have done a better job. Part of why I object to him is that he's held up as a role model. Someone to aspire to be like. As I see it, he seems like a conservative defender of an unjust status quo. But who knows? Perhaps if Aurelius had made more stronger moves against slavery, he would have been overthrown. The small changes that he and others had made would be reversed and the slaves would have had it worse. The virtuous act may have been to stay small, even though it may seem to people like me that he could've done more. Something he wrote about in the Meditations.

“You should not hope for Plato’s ideal state, but be satisfied to make even the smallest advance, and regard such an outcome as nothing contemptible. For who can change the convictions of others?” Meditations, 9.29.

Nevertheless, as I said, others had the will to turn the empire to Christianity, so I'm skeptical he was so powerless. Aurelius reminds of the white moderate Martin Luthor King wrote about in his Letter from Birmingham Jail. I feel like if the civil rights struggle advanced at the pace of Aurelius' timetable, I'd still be sitting at the back of the bus today.

"First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection."

Thanks for the reply and the podcasts. I'll try to see if I can get your book through my local library.

In reply to Slavery by Manumission

Aristotle and slavery

Following on from an earlier post, I listened to an Econ Talk podcast on slavery in the US.

There, the case was made that US slavery was different from Roman slavery. Roman slavery justified itself as spoils of war. US slavery justified itself by saying that blacks were inferior, they were like children and they were really better off as slaves in the US, than as heathen cannibals in Africa. That had consequences. It can be hard to get a slave to work. They have no incentive. In Rome, slaves were often allowed to be hired out and the slave was told when you've saved up X, you can buy your freedom. That was efficient as the slave had reason to work hard. In the US South, they couldn't take that approach as it would clearly undermine the view that blacks were like children who needed to be paternally looked after. It would show they were capable of planning, saving, hard work and follow through. So the whole practice in the US South was less productive.

Anyway, it reminded me of a question I have about Aristotle. In book 1, part V of politics, he says the following:

" ... from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule."

"It is clear, then, that some men are by nature free, and others slaves, and that for these latter slavery is both expedient and right."

Does Aristotle mean that some races - blacks, Spartans, Persians, whoever - are marked out for slavery, or that some individuals, whatever race they might come from, are marked out for slavery? If it is the latter, it might be charitably seen as a claim that some individuals have the personality traits suited to lead and that some individuals have the personality traits suited to follow. Though that would still fall short of a justification for slavery.

This could be one of those questions where it needs some ability to read the original Greek, or to have an extensive knowledge of the entire Aristotle oeuvre.

In reply to Aristotle and slavery by Following up

Aristotle and slavery

That's a great question especially since I discuss it only rather briefly in episode 48. This is a controversial passage in Aristotle, but one thing to note is that he does not invoke the concept of "race" and when he explains why some people (non-Greeks, basically) are "natural slaves" he does so in terms of climate and other environmental factors. So perhaps someone from a natural slave society, like Persia, whose children were conceived and grew up in Greece may not be natural slaves. In any case he does justify it in terms of inborn traits, not in what you are describing as the "Roman" way, but without using the notion of race.

In reply to Aristotle and slavery by Peter Adamson

Aristotle

Yes, I should probably have said "peoples" instead of "races" in my question. As I understand it, race is more of a modern notion and one that is contested by biologists today. We, or the biologists, can divide humankind up into genetic clusters or groups, but it's fairly arbitrary. They could divide us up into two groups, two hundred or two million. There isn't anything special about the races we might speak about in everyday use. How people self-identify or are socially identified is something else, beyond biology. Also, as there is more genetic variation within Africa than outside, it might be said there are more races within Africa than outside, which would probably run contrary to everyday use. That's my limited understanding. If Aristotle is dividing humankind up into peoples and talking about inborn traits though, he's not far from talking about races, even if that notion is an anachronism and even if he acknowledges environmental factors, a rose by any other name ...

Leaving that sensitive issue behind, but staying with Aristotle quickly, apologies if this is not the best place, I've heard it said that Aristotle has referred to humankind as the "political animal", the "rational animal" and the "social animal". Having looked this up while I was thinking about Aristotle, it seems that in different places he calls humankind the "political animal" and the "rational animal. He also says that humans are a special kind of political animal, because while bees and cows are political, in the sense that they live in hives and herds, they are not rational, that is not their form. Would you agree that Aristotle's views are best summed up by saying that humankind is the rational animal?

I'm also wondering how Aristotle might have been using the word "political". Words change their meanings over time. When I think of "political", I think of stabbing people in the back, being fast and loose with principles, breaking promises, Macchiavelli, being entirely self-serving to get you or your group more power and a better position in the status hierarchy. When I think of "social", I think of people being drawn to one another, enjoying each other's company, cooperation for the common good, self-sacrifice, bonds of affection, being stronger together than alone, for many the social may be what makes life worth living. When Aristotle speaks about the "political animal" is he closer to meaning the way I described the "political" or the way I described the "social"? Perhaps he thinks both are an inseparable part of communal living?

Thank you so much for your efforts in making the podcasts. It's wonderful series. Very much appreciate you also responding to questions, especially as you may have been asked the same kinds of things many times before. In the general comments I can see there is a show planned about Babylon, I'm looking forward to that :)

In reply to Aristotle by Following up

"Political" animal

It would certainly be fair to say that for him humans are the only rational animals, but that is not all that he means or primarily what he means when he says we are "political." The point of that is that we are the animals that congregate in a "polis" i.e. a city state. So on a minimal reading, which I would favor, it just means that we have a (natural) tendency to live together in a state setting, in contrast to other animals which may be social but don't have states with constitutions, etc.

Thanks for the kind comments at the end by the way - I love interacting with listeners here on the website, it is the only way I find out how the podcast is being received and not just falling into the void of the internet!

Add new comment