132 - Eye of the Beholder: Theories of Vision

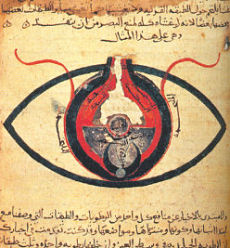

Ibn al-Haytham draws on the tradition of geometrical optics to explain the mystery of human eyesight.

Themes:

• P. Adamson, “Vision, Light and Color in al-Kindī, Ptolemy and the Ancient Commentators,” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 16 (2006), 207-36.

• D.C. Lindberg, Theories of Vision from al-Kindi to Kepler (Chicago: 1976).

• D.C. Lindberg, Studies in the History of Medieval Optics (Aldershot: 1983).

• M. Meyerhof, The Book of Ten Treatises on the Eye Ascribed to Hunain Ibn Is-Hāq (Cairo: 1928).

• E. Kheirandish, “The Many Aspects of ‘Appearances’: Arabic Optics to 950 AD,” in The Enterprise of Science in Islam, ed. J.P. Hogendijk and A.I. Sabra (Cambridge, MA: 2003), 55-83.

• A.I. Sabra, The Optics of Ibn Al-Haytham Books I-III: On Direct Vision, 2 vols (London: 1989).

• A.M. Smith, “The Alhacenian Account of Spatial Perception and its Epistemological Implications,” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 15 (2005), 219-40.

Comments

HoP 132 - Eye of the Beholder: Theories of Vision

Peter,

This was a fantastic summary of the history of optics, a history I have always been interested in, esp. with my fascination with Italian Renaissance linear perspective, both as an art and a science. I esp. liked how you summarized earlier Greek thought on optics, which me was still a bit of a massa confusa as to who believed / taught what. Your tripartite breakdown of Plato (with later Stoic additions), Aristotle and the Atomists is finally a concrete conceptualization that nicely sorts things out. Nice to have clarified that it is Euclid that begins the geometric tradition of optics, at least as formal mathematical discipline, but as likely derived from the history of the Greek theater.

Side note: I was intrigued in that you addressed one of main pioneers of optics by his actual Arabic name, Al-Haytham, rather than by its Latinized form, Alhazen, esp. as you also mention his contemporary by his Latinized name, Avicenna, and not Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā.

(I confess, it took me a few moments to realize you actually WERE talking about Alhazen once I saw the Arabic name in the Further Reading section rather than just hearing it--i.e., "why is Peter not bringing up Alhazen?" Lo and behold, he is!).

Are you following any standardized convention here in the realm of scholarship as to which version of a name to rely upon? Or is this arbitrariness (agreed convention) even more arbitrary that it is solely one's preference, esp. length of the name might be an issue? (I confess, I'm so used to Alhazen as the name as when I first learned of him as an undergrad which James Burke's The Day the Universe Changed).

Again--just a great show. I feel, if not see, the illumination.

Rhys

In reply to HoP 132 - Eye of the Beholder: Theories of Vision by Rhys W. Roark

Latinized names

Dear Rhys,

Thanks, I'm glad you liked the show! Your question is one I was just thinking about, albeit in regard to whether I should call Ibn Gabirol "Avicebron" - my initial thought was obviously not but then I had the same worry you mention here about consistency. Basically the rule I think I am following is: use the real names, not the Latinized ones, except for two exceptions. These are Avicenna and Averroes (oh, maybe you could also count Maimonides). The reason to make an exception here is not that they had an impact on Latin (though they did) but because they are genuinely famous under these names, but not nearly as well known in the guise of Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd. After all I want people to be able to find these episodes and I think they are more likely to look for Avicenna than Ibn Sina. Apart from them though, I am using the Arabic names. Maybe not the most principled compromise but I think it makes sense for practical reasons.

Thanks again,

Peter

In reply to Latinized names by Peter Adamson

Latinized names

Hi Peter,

I agree on your rule of thumb on Arabic vs. Latinized names concerning Arabic scholarly culture, with Avicenna, Averroes and Maimonides certainly as notable instances as more famous Latinized names.

But isn't Alhazen in this camp too?

Now, this concern is purely trivial, but I am curious. Otherwise, I know that Alhazen (my pref.) is also Al-Haytham.

As they say on South Park, "I learned something today." (This includes the very nice, tidy history of optics summary).

Thanks!

Rhys

In reply to Latinized names by Rhys W. Roark

Alhazen

Hi Rhys,

Well, the thing is that I've worked on optics in the Arabic tradition before (see the bibliography above) so when doing that I got used to seeing him referred to as Ibn al-Haytham and just automatically called him that. In fact I almost forgot to mention that he was known as Alhazen in the script! You may be right that he'd be more commonly known as Alhazen among non-Arabists, but to be honest, I doubt he is really "famous" under either name. Though he deserves to be.

Cheerio,

Peter

vision in renaissance magic theory

I would love to see the topic of vision revisited as an influence on renaissance magic theories. Suggested reading:

Vanities of the Eye - Stuart Clark

Eros and Magic in the Renaissance - Ioan Couliano

The Alchemy of Light - Urszula Szulakowska

John Dee's Natural Philosophy - Nicholas Clulee

Seeing the Word - Hakan Hakannson

Robert Fludd and the End of the Renaissance - William Huffman

In reply to vision in renaissance magic theory by Ted Hand

Light and Renaissance magic

Thanks, good suggestion! I'll put it on my to do list along with this helpful bibliography. (Also worth a mention for the reception of Arabic views on light is Robert Grosseteste who will certainly get an episode.)

Can you share transcripts? Please

I'm a foreigner, but I'm studying philosophy now. It's so great if you can share us your valuable materials... Thanks!

In reply to Can you share transcripts? Please by thang

Transcripts

The scripts will actually be published as a series of books, so the written version will be available in due course. (I'd rather not make the scripts themselves available publicly for the obvious reasons, plus the fact that they are a bit messy before being cleaned up for the book version.) In the meantime thanks for listening!

Peter

science as a philosophical branch..

Thank you for this Episode again! But I was a bit surprised not to hear of Ibn Haytham's contribution to the development of the Scientific Method. Due to his quantitative, empirical and experimental approach to physics and philosophy, he is considered the pioneer of the modern scientific method and of experimental physics, and some have described him as the "first scientist" for that reason. His Book of Optics has been ranked alongside Isaac Newtons's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica as one of the most influential books ever written in the history of physics...

Ibn al-Haytham developed rigorous experimental methods of controlled scientific testing in order to verify theoretical hypotheses and substantiate inductive conjectures...

Ibn al-Haytham's scientific method was very similar to the modern scientific method and consisted of the following procedures:

1) Observation,

2) Statement of problem,

3) Formulation of hypothesis,

4) Testing of hypothesis using experimentation,

5) Analysis of experimental results,

6) Interpretation of data and formulation of conclusion,

7) Publication of findings.

George Sarton, the "father of the history of science," wrote in the Introduction to the History of Science:

"[Ibn al-Haytham] was not only the greatest Muslim physicist, but by all means the greatest of mediaeval times.”...

I know this is a podcast focusing on Philosophy but I don’t see Science as a separate subject emerging independent from Philosophy. Rather Science is the product of Philosophy, like any Philosophical Theory produced by Philosophers, and are hence in my opinion to be dealt with as well in the subject of Philosophy. The Scientific method is rather a tool for Philosophers to test their own theories and develop a more sophisticated view on the reality of the physical existence. It is the tool to classify the realm in which the "bodies" exist. Furthermore their can be also a legitimate critic pointed out on the view how far actually Science can be the Ruler to Truth and Knwoldge itself. Are we already that blindly convinced that Science is the gate to true Knwoledge and Wisdom? Or did we just stoped thinking and relfecting about the Universe. I really see Science as philosophical model and theory rather than something oppsoing Philosophy. I think it would be amazing if you could also tackle the issue in one of your episodes of the history and evolution of philosophers and their methods of acquiring new methods of knowing, collecting knowledge, and the production of new knowledge itself and formation of theories. With best Regards, Yunus

In reply to science as a philosophical branch.. by yunus

Ibn al-Haytham

Funny you should mention this, because I am just starting to read up on Roger Bacon whose ideas about scientific method were influenced by Ibn al-Haytham (aka "Alhazen"). So I will get another chance to touch on this then. I think we should be careful not to ascribe more of the modern scientific method to these figures than can actually be found in them, but certainly we find in Ibn al-Haytham careful testing of hypothetical theory by observation, if not actual experimentation in the later sense.

By the way, a quick request/suggestion: you might want to keep your comments on the site a bit shorter, I can't imagine that many other users are going to read them in full if they are this long, plus it takes up a lot of room on the pages where you have been posting which makes it harder to scroll down to see later comments, etc.

Thanks

It's fascinating that I hadn't heard anything about al-Haytham until this episode. He was also featured in the Jim al-Khalili series Science and Islam. I had been thinking it was a result of British parochialism. I knew about Newton and his optics, but then I also knew about Einstein, Galileo and Davinci. There's a Chinese figure called Su Song and I've heard it said that Davinci is Europe's Su Song, as opposed to saying Su Song is China's Davinci. As I hadn't heard of al-Haytham or Su Song, maybe it's European parochialism.

As I see it, pun intended, explaining optics is one of the breakthrough moments. He might not have explained how we see, he would've had to have explained visual processing in the brain to do that, but he did explain how the outside visual world gets inside us. Curious too how one of the old theories, that parts of what we look at make their way to our eyes, ever gained traction. The things we look at don't seem to erode. It reminds me of a joke I was told looking through a telescope: don't look too long, you'll wear it out.

Seeing when you are not alone

Hi Peter,

I'm curious about how these ancient theories of vision would account for sight with more than one observer.

The first question is, how do extramissionist theories of vision would deal with more than one person seeing? Do visual rays interact or interfere with each other? Would other people's eyes not appear as shining or glow in the dark at least for Plato, since it is the similarity between the fire streaming from the eyes and light that creates a connection that generates a motion in the soul? Can I light a room if I look hard enough or have enough people looking at it?

The second is if there is any relation (perhaps present in philosophical texts) between these theories of sight and ancient superstitions like the evil eye?

The third is how do these theories deal with liminal cases for example blindness or nocturnal animals that appear to be able to see in the dark. If blindness is caused by the incapacity to produce visual rays, could I use my visual rays to help a blind person (who perhaps lacks the capacity to produce their own) to see? Can someone else "borrow my walking stick" to borrow one of the metaphors in that episode?

Hope you can illuminate me with your insights,

Jorge.

In reply to Seeing when you are not alone by Jorge

Vision

Great questions! Actually I know an ancient text - it's in Galen and was transmitted into Arabic - which cites the fact that some animals' eyes glow in the dark as evidence for the Platonist extramission theory. Bear in mind though that the visual ray is not itself light: it is not like flashlight but needs to meet a medium, or strike a surface, that is itself already illuminated.

The worry about visual rays entangling in the medium is a good one but I think rays' being immaterial, or nearly so, made this not such a problem - that objection arose I believe but only against atomist theories, since there it looks like the atomic images could collide.

Evil eye: yes, that does connect up and a similar context is falling in love. Some of the Renaissance theories of love I suggested in a recent(-ish) episode, like by Ficino, invoke the Platonic visual theory to explain how the gaze of the lover makes them affected by the beloved.

Add new comment