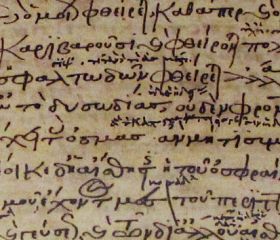

317. Made by Hand: Byzantine Manuscripts

Without handwritten copies produced by Byzantine scribes, we would know almost nothing about ancient philosophy. How and why were they made?

Themes:

• C. D’Ancona (ed.), Libraries of the Neoplatonists (Leiden: 2007).

• D. Harlfinger, Die Textgeschichte der Pseudo-Aristotelischen Schrift Peri Atomon Grammon (Amsterdam: 1971), ch.2.

• C. Holmes and J. Waring (eds), Literacy, Education and Manuscript Transmission in Byzantium and Beyond (Leiden: 2002).

• H. Hunger et al., Die Textüberlieferung der antiken Literatur und der Bibel (Munich: 1988).

• O. Primavesi (ed.) and K. Corcilius (trans.), Aristoteles: De motu animalium. Über die Bewergung der Lebewesen (Hamburg: 2018).

• L.D. Reynolds and N.G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars: a Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (Oxford: 1991).

• N. Wilson, “The Libraries of the Byzantine World,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 8 (1967), 53-80.

Comments

Had Byzantium survived

Had Byzantium survived another 50yr we would also have printed texts. It’s sad that the great empire fell when it did. :(

Lectio difficilior potior - the principle suggests that the more unusual one is more likely the original

That's from Wiki, and more or less it is how quoted scholars further down the page refer to it, as they highlight its pros and cons.

It seems the principle would be better thought of as something like, 'The more unusual or difficult variant of a text should be preserved above others only if all other possible or likely interpretations can be derived from it.'

Thoughts?

In reply to by E.S. Dallaire

Lectio difficilior

Well first of all this, like other philological rules, is an "all else being equal" kind of guideline - it's not like, the weirder a reading, the more we should be inclined to adopt it, regardless of other considerations e.g. meaning of the passage. I also wouldn't quite agree with the requirement that other readings need to be derivable from it, for instance one kind of lectio difficilior might be that one text has a word that another one just lacks, and it makes no sense to think of the absence of the difficult word deriving from the word (unless you think of a scribe skipping it as a kind of derivation). But with those caveats I basically agree, in that the most usual case would be two words that look similar and we are preferring the more rare or awkward one on the assumption that a scribe may have intentionally or uninitentionally have revised it to an easier reading.

In reply to Lectio difficilior by Peter Adamson

That makes sense. I was

That makes sense. I was thinking after I posted that my formulation was more 'big picture' than were the minute grammatical/syntactical/etc. decisions which scribes must usually have faced.

'All else being equal' - I love it

Thank you for the episode!

Praise of episode

I found today's episode fascinating and answered some questions I have had but never took to the opportunity to look at. I have told all my friends about the series (and my more mature students) and some have even thanked me later after listening to some episods. I thought this episode particularly interesting (I am more a historian than a philosopher) and I await next week's episode with great interest.

In reply to Praise of episode by Paschal Scotti

Thanks

Oh good, glad you liked it! I also learned a lot doing the research for this script.

And thanks for recommending the series to others!

sampling bias....

An interesting example of selective transmission of texts in modern times can be found in the library of the Rugby Colony in East Tennessee. The colony was founded in about 1880 by Thomas Hughes, the author of Tom Brown's Schooldays as a refuge for second sons of the nobilty who had fewer career options than their older brothers. The first librarian for the town sent out a request to vitually all publishers of books and periodicals in America and England for samples of their current catalogues. Thus, the library's collection repressents a nearly complete slice of what was in print for several years in the early 1880s. The commune failed. The town remains. The library with its collection is intact and available for study as a time capsule full of the materials most libraries quickly discard: seed and clothing catalogues, journals with the latest farming methods, novels that no one bought,

https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4007/

Applause

Great piece showing the importance of philology to the history of philosophy. Thank you for this. It is so important, but you rarely find introductory explanations of the most simple concepts and necessities of philology.

I want to add one thing just to make it clear: Modern-day Islam haters try to make up the case that the cultural breakdown of antiquity and the loss of many ancient texts happened especially and almost only because "the Muslims" cut-off the supply of papyrus. This is nonsense, of course. The shift of the predominant writing technology away from papyrus towards the use of parchment happened clearly before Islam even came into being. Inner conflicts of the Christian world such as political and economic turmoil and the difficulties of Christianity to arrange with pagan scholarship played the essential role, not any influence by "the Muslims" (who, by the way, were not so reluctant to embrace pagan scholarship, at least not in the first centuries).

In reply to Applause by T. Franke

Papyrus

Yes, that's definitely true. The Muslims would have been hard pressed to force a shift to parchment, given that they weren't yet on the scene for a couple of hundred years! Glad you liked the episode, hope you also enjoy the deeper dive with Primavesi in the next installment.

Aristotle retrieval from Byzantium vs Andalusia

Hi, you mention towards the end of this episode that the 1204 sack and subsequent occupation of Constantinople gave an opportunity for Latin scholars to copy or steal Greek manuscripts during the 13th century and that this lead to a revival of Latin interest in Aristotle.

How does this revival of Aristotle interest compare in significance to the one caused by Aristotle's reintroduction to Latin via Arabic in Spain?

In reply to Aristotle retrieval from Byzantium vs Andalusia by Xavier Young

Retrieval of Aristotle

Actually there is an episode on that other recovery of Aristotle, here:

https://www.historyofphilosophy.net/latin-translations

I think that the two dimensions of the translations are both very important, and complementary. In both cases, also, one should bear in mind that it is not just Aristotle that comes in but also commentaries, e.g. Averroes from Arabic, Eustathius from Greek; and philosophers who were not writing commentaries but who did powerfully influence the further development of Latin philosophy when they were translated, like Avicenna.

Add new comment