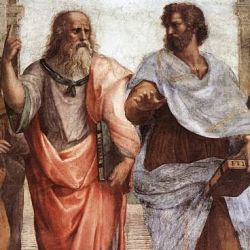

38 - Down to Earth: Aristotle on Substance

Posted on

Aristotle rejects Plato's Forms, holding that ordinary things are primary substances. But what happens when we divide such substances into matter and form?

Themes:

Further Reading

• M.F. Burnyeat, A Map of Metaphysics Zeta (Pittsburgh, PA: 2001).

• M. Frede, Essays in Ancient Philosophy (Oxford: 1987).

• M.J. Loux, Primary Ousia: An Essay on Aristotle's Metaphysics Ζ and Η (Ithaca, NY: 1991).

• T. Scaltsas, D. Charles, and M.L. Gill (eds.), Unity, Identity, and Explanation in Aristotle's Metaphysics (Oxford: 1994).

• M. Wedin, Aristotle's Theory of Substance: the Categories and Metaphysics Zeta (Oxford: 2000).

Aristotle

..

..

Comments

Substance vs. Attributes

I've been listening to your podcasts for the last couple of months. I'm planning on catching up to you but I just finished this one. Thanks for your work.

Previously, I had been taught that Aquinas took "substance" to be that to which "attributes" attach, like pins which attach to a pincushion; making substance (the pincushion) different from the attributes (the pins). A given substance would, itself, be attribute-less as the pincushion, itself, does not consist of the pins.

Is this also Aristotle's view? Do you think I have misunderstood Aquinas?

In reply to Substance vs. Attributes by LUCAS MINER

Substance

I'm afraid that is not really a correct summary of what Aquinas thinks (or Aristotle). You're overlooking the distinction between substantial and accidental attributes. The basic subject of predication, for both of them, is a substance which is a combination of matter and substantial form - the form brings all the essential/substantial attributes (e.g. living and rational for human). So it is not a "blank subject" that underlies accidental predication but rather the whole substance, e.g. a human. Most attributes are then accidental (tall, bald, in the marketplace, etc.). Thus, crucially, the substance in itself already has all the essential, but not the accidental, features - it is not in itself bereft of properties.

The idea of a "bare particular" which is like your pincushion view does come along later in the history of philosophy, like in Locke, but it is very un-Aristotelian. The only exception might be that if you ask, "well hang on, what is the substantial form predicated of?" then the answer is "matter," so in the case of humans that could be flesh and bones. Then you can ask, "what are the forms of flesh and bone predicated of?" and if you keep pushing then, on some interpretations of Aristotle including Aquinas', you will get down to prime matter which is just bare potentiality for form and underlies the elements. Still the basic situation for them is form+matter = substance, which is then subject for all accidents.

philosophy

I like it.

Aristotle on the union of body and soul

As mostly discussed by many philosophers descartes union of body and soul is like form to matter in Aristotle, but regarding to this problem I want to know can we go further and say that Aristotle is a functionalist, or he believes in the soul as the immortal form that can exist without the matter?

In reply to Aristotle on the union of body and soul by Ali Sanaeikia

Functionalism

That is a matter of huge debate. Actually I think you mean something more general than "functionalism," you just mean whether Aristotle thinks the soul is somehow dependent on the body? (Because not only a functionalist could say yes to this question.) There is also a debate about whether he is a functionalist but that is a more specific issue about how he thinks cognitive processes work.

Anyway, in general the ancient and medieval reading of him was that the soul can survive without the body because intellection, he says explicitly, requires no bodily organ. So we should be able to think after we die, still. But most if not all modern day interpreters think that they were wrong and that Aristotle would have the soul expiring with the body.

Forms: Universal of Particular?

After reading through the Metaphysics, I can’t help but think that Aristotle’s criticism of the Forms regarding the particular vs. universal distinction is a poor one. This seems like a categorical error to me. To say that something is universal merely denotes a relation between that sort of character and it’s subjects. But this relative predication cannot speak to substance. Otherwise, we’d be able to say that the sun or God cannot be particular since they are universal to everything else. A case that’s more intimate to Aristotle’s thought is the relation between body and soul. Hiawatha’s soul is a particular in that it is her substantial form, but her soul is universal in that it belongs to all of her body. Not to mention, to say that something cannot be a ‘this’ because it is a ‘such’ leaves Aristotle’s own philosophy open to attack in terms of ontology and epistemology. As far as I can tell, Aristotle plainly did not pay careful enough thought to the status of universals.

In reply to Forms: Universal of Particular? by Tim Petzold

Aristotle on universals

Well, as the rest of this podcast series shows this is not an easy problem - it becomes one of the most central debates in the medieval period for instance. But I think you are giving Aristotle short shrift. In the Metaphysics there is actually a passage where he makes a distinction between the individual sun and the universal *sun* which would also apply to, or be instantiated by, a second or third sun if these existed (though they don't). This shows that what he means by "universal" is not really what you are assuming he must mean. It sounds like you think universal means nothing more than "being present in more than one thing," but Aristotle would never say for instance that water is "universal" in a sponge because every part of the sponge is wet (nor does it make sense on his usage to say that soul is "universal" to its own body, as you suggest). The relation is rather that between a general character and its instances - modern day philosophers would say "type" and "tokens". So I think there is no doubt that his distinction is an important one that he makes clearly and well; the only question is what ontological status the universals have. And that is a difficult interpretive issue since he is much less clear on this, and may even say different things in different places.

Earth

if substance implies a seperable entity, can the earth have primary substance? On the one hand, it could be seen as a. collection of objects or substances, but on the other, it is and is part of an integral system where no one thing could exist apart from the others for very long. If the earth wandered of course, it wouldn't no longer be earth.

In reply to Earth by Mel

Substances vs heaps

That is a good question. Aristotle clearly sees organisms as the best example of primary substances, and so things like artifacts and lifeless bodies have a rather indeterminate status. But it seems like a pile of earth for him is a mere "heap" because it has no determinate form (like, you can add earth or take it away without really changing its nature); that would also apply to thinks like clouds, puddles, etc.

Is substance a category

Is it reasonably to classify substance as one of the categories? As long as substance by definition is not a predicate and it is a conditional for the other categories ("presupposed"), shouldn't substance be "categorized" differently?

In reply to Is substance a category by thomas helle-valle

Substance

Yes substance is one of the ten categories. Bear in mind that the idea is not that "substance" is itself a predicate, but that substance terms like "animal" or "human" are predicated. Just as in the category of color, the predicates would be things like "blue". Whether "substance" and "quality" are themselves predicates is another issue which is a more narrow, technical question not taken up by Aristotle.

philosophy

Do you think Aristotle's substance is a practical solution to the problem of the one and the many?

In reply to philosophy by Thaddeus

Substance

Well, that's kind of a big question but basically yes: the distinction between essential/substantial and accidental properties is especially powerful here because it allows him to explain how a single thing can persist through change, as when Socrates survives as one thing while being first at home and then in the marketplace (one substance = Socrates, two locations = accidents).

philosophy

Where in particular in the Metaphysics does Aristotle make explicit mention of substance as a solution to the one and the many?

In reply to philosophy by Thaddeus

Substance and one/many

Well, you can look in the "middle books" i.e. books 7-9; book 9 ("Iota") is especially interested in unity. But that is really difficult stuff so if just want the basic view, which I was explaining in my previous comment, you'd be better off with Physics book 1, especially the part at the end about how many principles there are, also the bit in that book refuting Parmenides.

philosophy

Does Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas both treat substance in the same way?

In reply to philosophy by Thaddeus

Substance in Aristotle and Aquinas

Aquinas would probably say yes! And broadly I think the answer is in fact that he is following Aristotle pretty closely on this topic; even the apparently large difference that Aquinas accepts the survival of the soul after death isn't that big a difference, since he stresses the need for bodily resurrection to restore the human substance to its full unity as a combination of matter and form. One difference though would be that Aquinas also is drawing on Avicenna who adds the essence vs existence distinction, which is not in Aristotle.

Add new comment