Transcript: 410. Ann Blair on Jean Bodin's Natural Philosophy

Note: this transcription was produced by automatic voice recognition software. It has been corrected by hand, but may still contain errors. We are very grateful to Tim Wittenborg for his production of the automated transcripts and for the efforts of a team of volunteer listeners who corrected the texts.

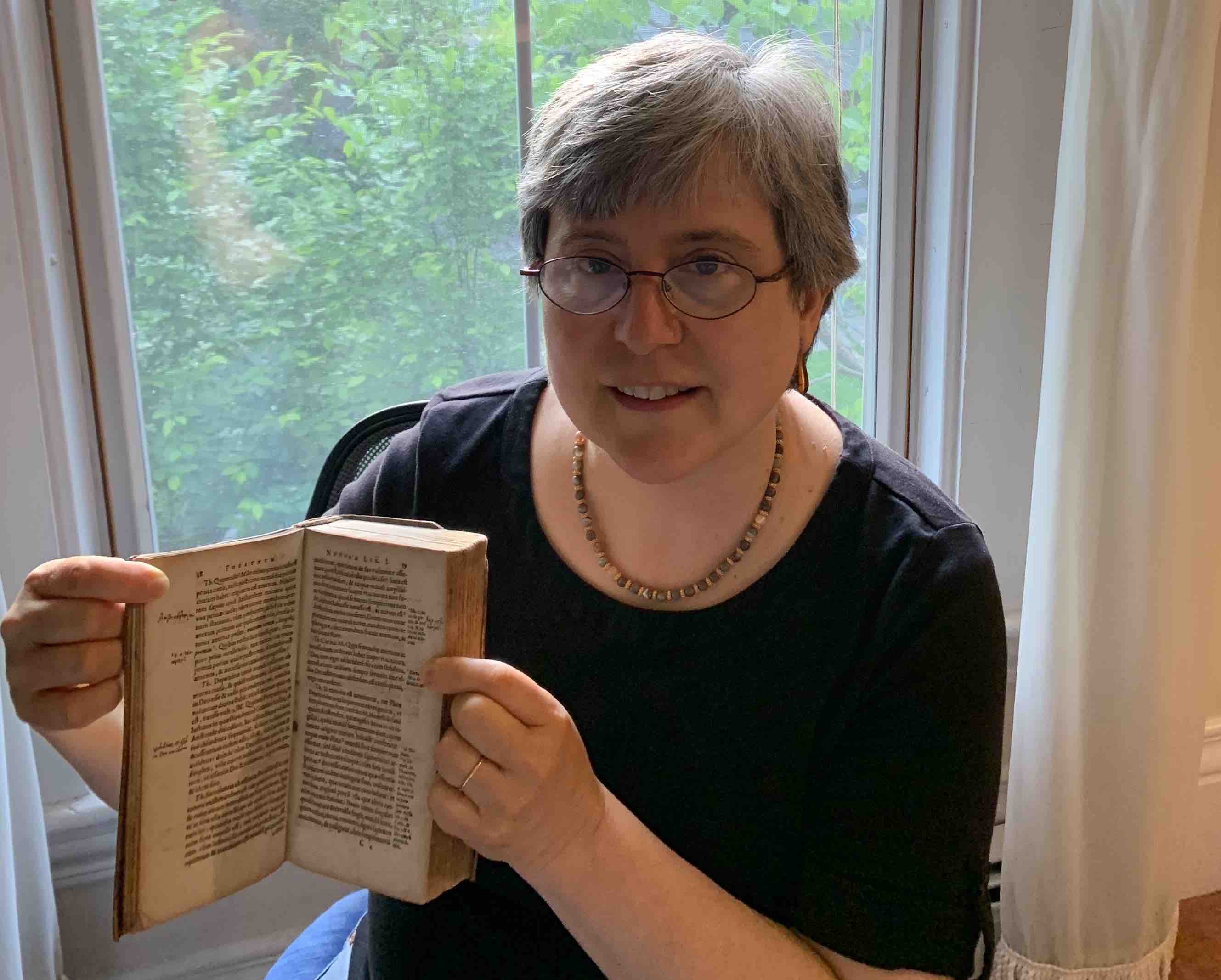

Peter Adamson: We're going to be talking about Jean Bodin, which you can probably pronounce better than I just did, whom we covered in the previous episode. So the audience has already heard me attempting to pronounce his name numerous times. And you are an expert on him because you wrote a book about his work on natural philosophy, which is called The Theater of Natural Philosophy. And I was curious if you could start by telling us something about the title, like why theater, obviously, but also why natural philosophy. So what did they mean with that phrase in that era?

Ann Blair: Theater is a lovely metaphorical title, which is part of a cluster of metaphorical titles that people love to use in this period to describe books that tried to encompass a wide scope, in a way to bring it to your mind, your eyes rapidly. And so, for example, we'd call them encyclopedias today, I'd say. But that term, although it was coined by Rabelais, among a few others in the early 16th century, was very rarely used as a title of a book. Instead, for example, Vincent de Beauvais in the 13th century calls his encyclopedia a mirror, the Great Mirror of natural philosophy. So Bodin’s is a theater. Others have gardens. There's the bundle of flowers. So all these lovely metaphors describing this idea of bringing together all kinds of things for you to see. But Bodin spins his analogy with an emphasis on divine providence. He says in his dedicatory epistle, the theater of nature is nothing other than a sort of table of the things created by the immortal God, placed before the eyes of everyone, so that we may contemplate and love majesty, power, goodness, and wisdom of the author himself and his admirable providence. So that's his project, really. And you're absolutely right. The other term in there is natural philosophy, which is our term, really. He calls it the Theater of Nature. But natural philosophy was an actor's category, which covers the study of nature, what we might call science. But of course, that term is much more recent. It meant certain knowledge at the time, but the term “scientist” dates from the early 19th century. So I think natural philosopher was the main label that people used about themselves when they were busy talking about science. Of course, Jean Bodin, and your pronunciation was perfect, is principally known as a political philosopher, not a natural philosopher. So my study really is about a little-known work, his last work published in 1596, the year of his death, of a man who was famous already for something quite different, really. Although I think there are parallels. Everything is much of a muchness. His philosophy hangs together. He's also interested in the hand of God at work in human history. And here he is interested in the hand of God at work in the natural world. And he has a very similar method of working, which is piling on examples of many different kinds, from which then he tries to reach conclusions. I think he's got more strident conclusions in his political philosophy because he's addressing current issues of politics and a crisis in French government, really due to the civil wars caused by religious acrimony, not just between Catholics and Protestants, but between Catholics and Catholics, extreme Catholics and less extreme Catholics. And Bodin was definitely one of the politiques, sort of the moderate Catholic camp. So in his natural philosophy, he doesn't really have a strong single message. He's not trying to resolve a problem. Although his basic point is we have a crisis of natural philosophy because Aristotle, the foundation of natural philosophy as studied in universities, as studied by many philosophers in the Middle Ages and for much of the Renaissance, he perceived to be impious, not properly pious philosophy. And so Bodin is setting out to create an alternative, but rather than really coming up with an alternative, what he's really doing is just poking holes in Aristotle.

Peter Adamson: And he does that on a very wide range of topics and it's extremely diverse. As you said, there's all these examples, there's all these topics. How would he have gone about composing a work like this?

Ann Blair: Yeah, that's a great question. And we do not have any manuscripts of Jean Bodin, partly perhaps because he had them destroyed near the end of his life. He was worried about being found to be heretical or at least to be suspected of impolitic views. So he certainly was living in a difficult time and very conscious about his legacy. So we have no manuscripts. But I argued from the work itself about how he plausibly took notes from his readings under topical headings from which he then drew to compose his natural philosophy. But equally well, one can surmise his political philosophy, his Six Books of the Commonwealth.

Peter Adamson: So this would be maybe comparable to a commonplace book. This is like, for example, we looked at work on politics by Lipsius, which is also a commonplace book, where I saw these quotations from antiquity. So it's almost like they have what, node cards or index cards or something, and then they kind of collate them together and that's how they make the book. Is that how it would work?

Ann Blair: That's the hypothesis. I wouldn't think they were cards, actually, although there is evidence for people cutting up slips of paper when they want to do something really serious like indexing a book. But I would think of it as a notebook, where you would put a heading of something that was interesting to you at the top of the page, and then you add into that page quotations from other authors you've encountered, but also possibly, given what Bodin puts into his book, observations of his own, things he'd encountered and talking to people. And so he's collecting toward a work that he may change his ideas about, as he goes along. So it's not at all clear how much is he drawing everything from a commonplace book and how much of the commonplace book is he reusing. Those are the kinds of questions we can't answer without having some physical evidence. But we have commonplace books from other authors, so it's quite plausible that that's how he gathered his material. And I could imagine – this is a late work, so he's got a lot of stuff in there on natural philosophy. So the book itself is about 600 pages and an octavo volume. So it's a small format, and it's divided into five books. And it's ordered by book one on the principles of nature, very much Aristotelian topics about place and motion and the elements and causes and so forth. And then he moves up the chain of being, from the meteors and metals and minerals to plants and then animals and then humans with their senses and their souls. And then finally, he's got the heavenly bodies. So that's a pretty classic way of proceeding for talking about the natural world, as you say, the whole thing. In a small compass, that's the theater idea.

Peter Adamson: That makes it sound very well organized. But in your book, about this book, you say that in the Theater of Natural Philosophy by Bodin and also similar works by other authors, there's what you call a tension between order and variety. And I was wondering what you meant by that. And I guess I was also wondering whether this is, in a way, part of the anti-Aristotelian drift of what he's doing, because Aristotelian philosophy at least presented itself as being incredibly systematic. Whereas, although he has these headings, sort of moves through the cosmos, as you just said, it seems like under each heading, it's kind of a jumble of different things, right? And that could be because of the way it was written, as we were just discussing. But couldn't it also be that he just thinks this is how natural philosophy should work? So you should sort of make observations about a whole wide range of things and not try to force it into the scheme of the Aristotelian structure.

Ann Blair: Yeah, that's a great point. I agree that inside each of those books, it is very much stream of consciousness. And it's hard to tell why he treats certain things at length and other things not at all. That would sort of be driven by the material he's got, the observations he's got. And I like the idea that it is challenging the order of the disciplines, for example, as one would have studied them, the seven liberal arts, followed by the four areas of philosophy, which was another classic way of organizing an encyclopedic work. But I'd like to point out that really, this is a time when people experiment with lots of different orders. There's one historian who has argued he's identified 19 different systematic orders. I think one of the reasons is that order was thought to be super-important. You want to match the truth of things. And if you have the right order, then you'll be able to understand everything sort of by snap, almost miraculously. It'll just all come together and make sense. And you'll be able to retain it in memory. So there's this huge drive to get the order right. And I'd love to tell you about a guy named Theodor Zwinger, who wrote another work entitled Theatrum, which was even larger than Bodin’s, and covered natural philosophy, but also human history. It was called the Theatrum Humanae Vitae, the Theater of Human Life. And it was 1.5 million works at first. And then he revises it three times, and it gets bigger and bigger each time, down to triple the original size. And each time, he rearranges the whole thing. And it is so complicated. But he's so proud of his order. He gives you branching diagrams, mapping it out. And he spent a huge amount of effort doing this. And of course, to us, honestly, it makes very little sense. He moves between binaries. He's got an ethical scheme. So he goes through the vices and the virtues, and he pairs them up together, and so forth. But why this order rather than another one exactly, is completely unclear. And what's kind of sad is I came across a wonderful quote of a contemporary, a dozen years later, who's commenting that Zwinger put an enormous labor, he says, into organizing the headings. But he says, I don't know that the fruit was equal to the labor. Indeed, the order is neither constituted accurately according to logic, nor is it such that you could refer all things to it, or find what you desire without great difficulty, unless you take refuge in the alphabetical index. And in a sense, that is the key to everybody doing whatever they want because you have an alphabetical index if you really want to find something. Of course, Bodin's book does not have an index. So he's forcing you to read his thing in order. But a lot of, I'd say, some of the liberties people take with order in the 16th century is made possible by the alphabetical index, which Zwinger has. He hasn't just one, but a few, three of them. And then, of course, another order, which just says, I'm not going to have an order. It's this self-consciously miscellaneous order, proud to have no order, because it offers, it boasts about the pleasure of variety, that you're going to have fun. You're going to be surprised by what comes next. And of course, if you do want something useful out of this, you can get it through the index. And so that is classic of, say, Erasmus's Adages. Certainly Erasmus's Adages, a collection of proverbs from antiquity with his commentary, is not the only book miscellaneously organized, but it was so popular, very widely reprinted and also abridged and imitated. That sort of gave cachet in the 16th century to the miscellaneous order. Of course, in the long run, the miscellaneous order did not become a thing. I see it as sort of a specifically Renaissance experiment. Because the order that does prevail, which Bodin does not use at all, is alphabetical order. And we can think about someone like Conrad Gessner, who is basically a near contemporary of Bodin, but who writes on fauna and flora, quadrupeds, reptiles, birds, fish. Each one of them is organized alphabetically. And he explains, he tells you why he does this. The utility of alphabetical order comes not from reading the book from beginning to end, which would be tedious, but rather from consulting it per intervalla, by intervals, intermittently, non-sequentially. And so it's fascinating he has to explain that in his front matter, but that's how he expects you to read. He's doing something new, which of course will become characteristic of what we think of as the modern encyclopedia. That's what we expect out of one of these things.

Peter Adamson: Right, because no one reads a modern encyclopedia cover to cover, and you can't read it, it's too long. So these works you were just describing, when you first were describing them, I was thinking, could anyone even use a book like this? And the answer is, you don't sit down and read it. You somehow navigate your way through it. And they're working on what you might call technologies of the book to help the reader do that.

Ann Blair: Exactly. I think Bodin's book in particular is not that big that you must consult it. But the Gessners and the Zwingers of the world are so huge that yes, that's the only way.

Peter Adamson: I feel a little sorry for poor Zwinger, doing all that work and getting told off for it.

Ann Blair: But he's a treasure trove. I mean, you can use the index now and you find amazing anecdotes. He didn't lack for hubris. He felt he was offering what God will see at the last judgment is all the behaviors of humans. So that's a different idea of theater, of bringing it all together, but also kind of like the people are on a stage. Whereas Bodin's theater is nature, is what's the stage that we're looking at and we're watching God through nature. We're appreciating his actions.

Peter Adamson: All the world's a stage, so to speak.

Ann Blair: Yep. That's the Shakespearean one, which yeah, they're all interconnected.

Peter Adamson: One thing that your description of how these books were written makes me wonder though is that it sounds like a very literary activity. So for example, if we're imagining them with these notebooks, presumably the notebook is next to the books that they're reading. So they're taking notes on their reading. And that isn't at all what we think of as science, right? So we think of science as going out and looking at the world. And that makes me wonder, is there any role of – experimentation would probably be too much to ask for, but what is the role of something like experience of actual phenomena in this kind of natural philosophy?

Ann Blair: There's very much a place for experience. And even in medieval natural philosophy too, experientia. People could bring in things that they've experienced personally or vicarious experience that other people have reported. So you're absolutely right that it's fundamentally a textual activity, a bookish activity, but it's very much about the natural world, and you want the text to match the natural world. And I'd just like to point out that Aristotle gets a bad rap for creating this system, which obviously is going to be overthrown in the course of the 17th century, except for logic, which persists a very long time, but Aristotle too did a lot of observing. He opened those eggs at various stages of the chick’s development, and he found some kind of fish in the Mediterranean that people didn't think existed until they found such a specimen in the 19th century. I love these stories of Aristotle the observer. So no one necessarily feels they have to be anti-Aristotelian just by observing. And I think it's true that it's the Renaissance Aristotle, the Aristotle the observer was less in the canon of Aristotle, the people read the Middle Ages and rather the parts of Animals and these other more empirical texts became known by the humanists and so forth. So in some sense, Bodin is heavily indebted to Aristotle – of course, he's got causes and elements and is very much speaking in Aristotelian terms, but of course to criticize a lot of the specifics of Aristotle. Sometimes he's doing targeted experience searching. So I love this example that he talks about whether the ostrich can digest iron, which is something that Pliny had said in his Natural History. So obviously this is an important question. He doesn't have a pre-theoretical idea like we would have. I don't think so – he just wants to know. So he said he has seen some ostriches brought to France and watched them be fed by the tamer. Nonetheless, I could not understand anything from the tamer.

Peter Adamson: Oh, the tamer speaks a different language.

Ann Blair: Yes, it seems there's a serious language barrier, but you can see Bodin seeking to find out whether the tamer served nails to the ostrich. I don't know. At other times though, he talks about, for example, he recalls his experience in the fish markets to support his argument that salt water is purer than fresh water. The fish of the ocean are bigger, better and more tasty than the others, as I experienced in Toulouse where fish are brought both from rivers and from the sea. So that's sort of his personal experience and possibly also talking to fishmongers, integrated into his book. So he has plenty of references to everyday experience or targeted experience. He's not exactly making any controlled experiments. And of course, sometimes experience shows some pretty weird things. Like he says, I saw a topaz, set in gold, broken in many places, to which the Toulousain attribute the power of changing color to signal danger. So that this stone has magic properties, and he's seen one. And so that's – it's not magic. It is the nature of the stone to do these cool things. So in that sense, of course, experience can be capacious, as we would say, by our lights. Of course, we come with all this baggage, well, that's not possible. And I think in the Renaissance, they don't have that. They're imbued with the omnipotence of God. Who are we as humans to say this isn't possible? Of course, God can give all kinds of properties to things. And of course, there's the magnet and iron, and they attract each other at a distance. How does that work? Why is it crazier to say that this stone changes color when it precedes danger?

Peter Adamson: When you describe him looking into things like can an ostrich digest iron nails – don’t try this at home, kids – it strikes me that if we were describing the motivation for that, I think the natural thought would be, well, he's curious. And that doesn't seem to fit obviously with what you've been talking about several times, which is this idea that his work is a theater which depicts the theater of nature, the point being to display God's providence and majesty and so on. And also, the word curious or curiosity, at least in the medieval period, was often used as a kind of accusation – like you're showing curiosity. Even in Augustine, I think this is present. So is there another tension there between what you might call idle curiosity and this focus on nature, something we already saw with Melanchthon actually, this focus on natural philosophy as a way of displaying God's might and justice and order?

Ann Blair: Yeah, I think there's a potential for tension. And Bodin does not use the word curious himself. Curious, you know, comes from cura for care. So curious could also mean just doing something carefully. Like even Samuel Johnson in the 18th century talks about curious reading, by which I think he means a very focused, careful reading. But I think actually, the whole focus on divine providence liberates people to feel that focus on nature is admiring God. And so it's not so bad. Basically, it's okay. It's a form almost of divine worship. And of course, natural theologians will play that up. But I see Bodin fitting into that tradition very much. He does, though, draw limits. He feels that humans shouldn't be idly trying to explain everything. And he does not like how Aristotle tries to explain everything, things like, for example, earthquakes, by exhalations that are trapped underground and burst out. Bodin feels that basically, he says you can go crazy through reasoning. And it's much better to just acknowledge that you can't understand that these are part of the mysteries of divine creation. Personally, he suggests that demons might be operating in earthquakes. So he's willing to bring in some supernatural, we would call supernatural. Of course, it's all through divine permission. So he's critical of Aristotle for trying to explain too much. And he says that humans should confess ignorance rather than hubristically coming up with crazy explanations, basically.

Peter Adamson: It sounds a little bit like he's trying to have it both ways. So if he thinks it's worth looking into something, like can the ostriches ingest iron? Do stones change color because they're afraid? Then he looks into it. But if Aristotle does it, then he's like, oh, Aristotle presumptuously looking into the secrets of God.

Ann Blair: I think you're absolutely right. He likes to criticize Aristotle. And he doesn't have a whole lot to offer in his place. So then he just offers confession of ignorance, admiring God, and we move on. And he only investigates stuff that he has something to say about that he's found interesting. He's not at all systematic. He doesn't say, okay, we've got to talk about X, Y, and Z, because it's out there in nature. He just talks about what he wants to talk about. Absolutely. I got a lot of insights into this book from reading a copy of the book that was annotated by a reader at the time, who read it from cover to cover. And that's quite unusual, as you point out, a lot of people would dip into a book, or they start really diligently annotating and then they stop after 30 pages or whatever. So this reader who's anonymous really did a great job all the way through. And the single most common comment he made in the margin was: Aristotle is criticized. So that's the Aristoteles reprehensis. He has that pretty much, when you count it out, on every fourth page, on average, he's got a criticism of Aristotle. So that's striking the reader as interesting about Bodin, that Aristotle is being criticized and he's pulling it out. I think that really is a nice insight into what readers found interesting and new and different about Bodin. Even if, like I said, he's got a ton of Aristotelian baggage, by our perspective. This is not mechanical philosophy by any stretch; it's very much Aristotelian. But he's poking, poking, poking at Aristotle whenever he can, making fun of him for the trope that Aristotle is obscure like a squid who sends out black ink so he can't understand anything. His prose is obscure, his explanations don't make sense. But what he offers in exchange is not an explanation of his own, or he might sometimes have one, like this whole business of salt water and fresh water. But many times he just chalks it up to the mysteries.

Peter Adamson: Is that true in general of 16th-century natural philosophy, that they are better at criticizing faulty explanations than giving good explanations? Or did they actually make some what we might now call scientific breakthroughs during this period?

Ann Blair: That's a good question. Obviously, in certain fields, someone like Copernicus comes up with this hypothesis, which he has very little evidence for and which creates a lot of problems, but which gives him a very satisfying explanation of something kind of weird, that the planets look like they're going backwards and stop night after night in their trajectories. And we consider that a huge breakthrough. I think at the time, there wasn't a whole lot going for it, except for those people who thought, ah, that's beautiful. That really makes sense in a very satisfying way.

Peter Adamson: Or Vesalius’s anatomy. So there are these sort of famous examples. But I was wondering more like if we trawl through these commonplace books on natural philosophy, are there tidbits of gold buried in there?

Ann Blair: Well, a lot of it is description. Conrad Gessner, for example, is apparently the first to describe the tulip, which came from the Middle East. And they do not classify things in a way that proved durable, let's put it that way. Sometimes they classify, say, birds by the kind of feet they have, the kind of beak they have. He's got birds that live in the dust. This is chickens and turkeys and so forth. And then they've got the web feet and the birds that fly and don't fly. But it's all bizarre, not systematic classifications. So that's where the index again comes in handy. If you really want to look at a bird, you might look in the index to find where it's being discussed, because it's not obvious, to us at least. And you provide all kinds of information like recipes for cooking chicken and the medical qualities of items that can cure things. So yes, very unsystematic. I think that's perfectly fair. Kind of heaping together a celebration of this diversity. And of course, the New World is part of that. Obviously, going to the New World and being aware that there are new species or, of course, wondering if they're new. Is there actually a Latin ancient term for this or not? And it's a judgment call. And even things within Europe, are they the same or not the same in different parts of Europe? So there's a lot of work really that goes on through the 17th century in the natural history realm, of trying to figure out matching descriptions and terms, Latin and Greek terms. But then we have vernacular terms, all the everyday in the languages that we think of now, French and Italian and so forth. But then the gazillion local dialectal forms. There was a lot of words to try to match up with reality.

Peter Adamson: Yeah, maybe it's better to think about it not so much in terms of breakthroughs that we would think of as exciting science nowadays, but think about it more in terms of what readers were getting out of these books at the time, because they obviously were getting something out of it. I mean, you don't read a 600-page book if you find it useless.

Ann Blair: Exactly. I do think that the anti-Aristotelian pose is really important because Bodin is not alone in this. He's alone in the specifics. But there are other philosophers of his time who are, first of all, realizing there's so many ancient philosophers – and Bodin drops a lot of names of ancient philosophers, I don't know exactly how much he knew about some of them, some of them I think he just knows secondhand. But this awareness that Aristotle was one of many, and why should we be so obsessed with him? Why should we trust him? Obviously, Aristotle was the backbone of the educational system and of university curricula from the 13th to the 16th century. But Bodin is busy sort of saying, well, you know, that's hardly an argument. And then other guys like, I don't know, Patrizi or Lipsius or Gassendi are busy looking to other ancient philosophers, whether it's Plato or the Presocratics or the Stoics or Lucretius and the Atomists, and saying, we can just get as good or even more pious philosophy from looking at these ancient philosophers. Why obsess with Aristotle? So I think it's an important moment of destabilizing Aristotle for a lot of people and creating some doubts. Of course, the curricula – and the Jesuits in particular go on saying that the Thomist synthesis is basically the key to having a pious philosophy and you will follow the mainstream – but in Protestant universities, Bodin was actually read and commented on, and it was part of having trouble with that Thomist synthesis and trying to think of alternatives. Of course, the big alternative was someone like Descartes, who also thinks he's offering a pious philosophy, but it's awfully different from looking at an ancient source and doing this whole textual analysis and commentary. And yet, I think it's part of the context out of which Descartes comes.

Peter Adamson: The anti-Aristotelianism is obviously a point of continuity with the 17th century. You mentioned a couple of minutes ago that the mechanistic philosophy that we're going to get in the 17th century is not really part of the story here in the 16th century. Are there other continuities/discontinuities you would point to, specifically with natural philosophy, in the 16th and 17th century?

Ann Blair: I think the idea that you see God through nature has a huge continuity. Someone like Robert Boyle writes the Christian Virtuoso. Even Descartes, you're seeing the laws of nature. You're seeing God through the laws of nature, or Newton through the laws of nature. Whereas others will emphasize you see God in every particular. You see God through the microscope, Hooke’s Micrographia, or you see God in the heavenly spheres. But that whole justification, that doing natural philosophy is a good thing, it brings you closer to God, is very long-lived, and it's continuous, I think. It actually reaches back, of course, to the Middle Ages as well, but just runs right through into the 18th century, and one could argue through Darwin, really.

Comments

Add new comment