Transcript: 116. Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò and Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò on Cabral

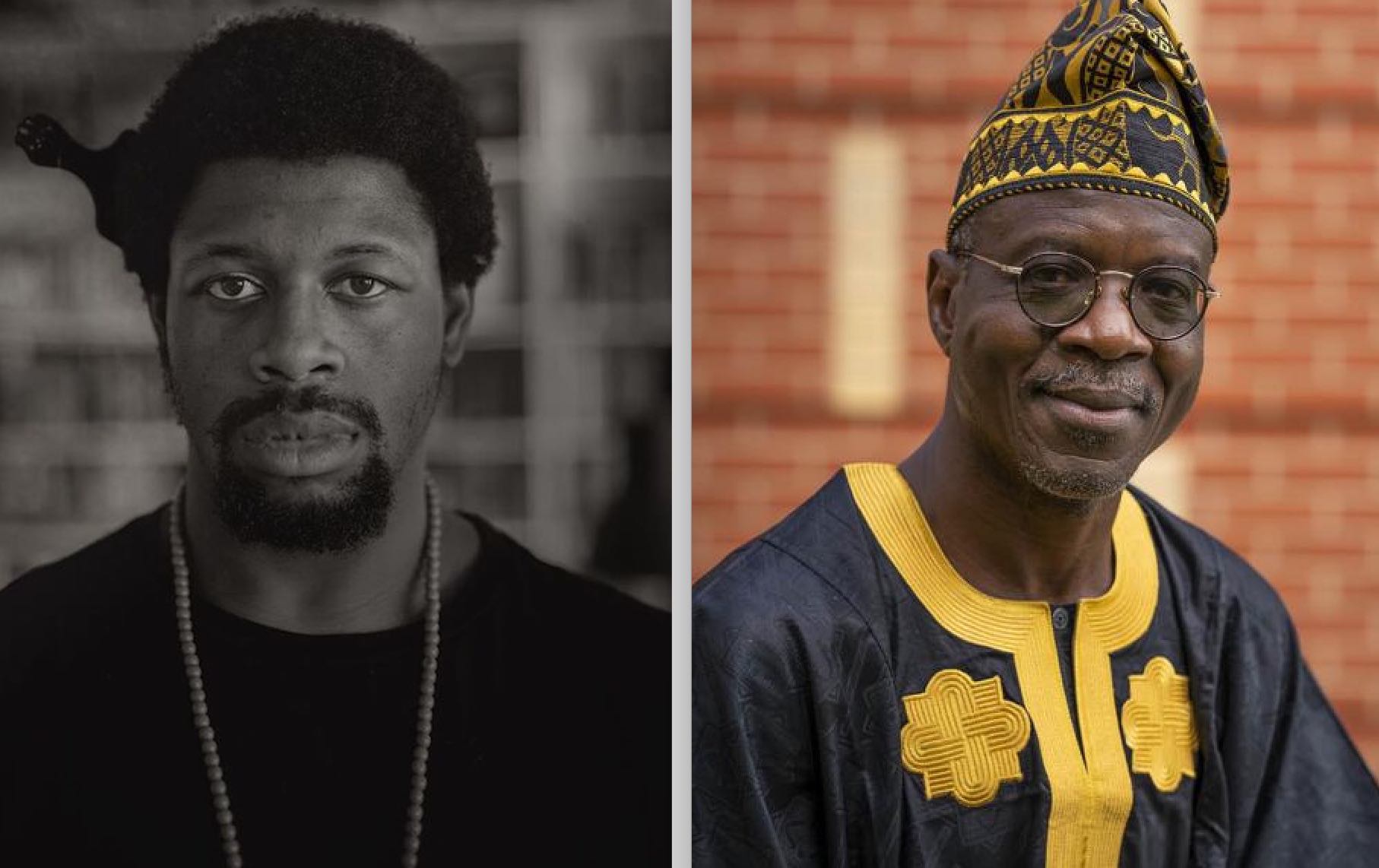

History of Africana Philosophy 116 – Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò and Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò on Cabral

Note: this transcription was produced by automatic voice recognition software. It has been corrected by hand, but may still contain errors. We are very grateful to Tim Wittenborg for his production of the automated transcripts and for the efforts of a team of volunteer listeners who corrected the texts.

Peter Adamson: So we have Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, who is professor of Africana studies at Cornell University. Hi Professor Táíwò.

Malam: Hello Peter.

PA: And I'm instructed to call you Malam. Okay. So Malam will be the, as it were, the elder Táíwò. And then we have Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, who is assistant professor of philosophy at Georgetown University. And we're just going to call you Femi. In so far as I need to call you anything. Okay, so having gotten that potentially confusing issue out of the way, let's turn to Amílcar Cabral and let's start by putting him in context. Where does he fit into the larger story of freedom fighter philosophers in the anti-colonial struggles of Africa? We've seen some other figures like this, like Fanon, Nyerere, and Nkrumah. Is he someone who fits into a pattern that's kind of begun by them?

Femi: I would definitely say that they're all cut from the same cloth. And they're contemporaries. It's gone as independence as first, but a lot of the independent struggles were really generational in the making. So I prefer to think of them as all being produced by a transnational, transcontinental kind of progression in politics over decades.

PA: And you agree with that Malam?

Malam: Yes, I do. The only thing I will add is that part of the problem has always been for me that people, including many African scholars, never really thought of them as thinkers. And when they thought of them as thinkers, they never thought of them as philosophers. And that battle is not over yet. And when it comes to somebody like Cabral, much of whose philosophy has to be reconstructed from party directives, instructions, community engagements. What I always ask people is, the history of philosophy is enriched by the history of pamphleteers from 18th century England. Much of what comes as original American philosophy is summons and pamphlets and creeds from all kinds of people. So why I don't want to reduce Cabral to that? I'm just saying that we should never give any inch to issues of pedigree. Yes. And that list is actually longer than what we have here right now, but we can just go with that.

PA: Right. But there's still a contrast between him and, let's say, Nkrumah, who wrote several books that kind of have on the face of it that they're philosophical works or works of political theory.

Malam: Honestly, not quite. And the reason why I say that is that once you take consciousness out, all of Nkrumah's writings are also what people want to dismiss as political writings, you know, instructions and so on and so forth.

PA: Right. So actually the same issue arises. And in terms of the intellectual background for Cabral himself, something that we tried to make clear in the previous episode is that he's responding to the Marxist or socialist tradition, and in particular, the place that Marxism had on colonialism. So maybe before we get into Cabral, we could try to sketch out the status quo before Cabral comes on the scene. So what was the orthodox Marxist position on colonialism insofar as there was one?

Femi: There's a few thoughts and marks about the contribution that colonialism makes to the world system. Maybe the most clear contribution that the colonies make to the world system, as Marx seems to envision it, is scale. The scale of industry and thus the scale of reach for capitalist exploitation is a direct result of the colonial vectors that the Western European powers had been making over the previous centuries. And the second major contribution that the colonies make beyond scale in the kind of market sense is maybe scale in a military sense. So you see not only in Marx the discussion of what conquest of the world, you know, what a proletarian uprising, global proletarian uprising would have to involve, it would certainly have to involve people in the colonized parts of the world, but it would also involve toppling the major imperial powers. This is something that especially the old school Russian Marxists, the Bolshevik party, the SRs were preoccupied with. What's the potential for revolution in the other parts of the world, in the backward countries as they were called in the parlance of the times? I think the thought most people had settled on, most people writing after Marx, but in the time of the Bolshevik revolution was that there would have to be revolution in the colonial centres first, and then it would be possible to make inroads in the so-called backward countries. But this is something that there was obviously a different kind of discussion about after the Second World War when the colonized parts of the world were the sites of revolutionary struggle.

PA: Okay, Malam, do you want to maybe build on that and perhaps also say something about how Cabral then modifies socialism as it had been passed down to him through the tradition?

Malam: Let me controvert the idea that he was part of that Marxist setup in Africa. I don't think there's evidence of that. Or like somebody like Agostinho Neto or Eduardo Mondlane. And in the conversation you and I were having before we started this conversation, if Cabral was part of that tradition, let's say when he went to school in Portugal, we're yet to have evidence of it because remember, Portugal was under a fascist dictatorship.

PA: Right, so talking about socialism was not encouraged, probably.

Malam: Thank you very much. Yes, there was a very buoyant Marxist tradition in different parts of Africa, beginning with the Sudanese Communist Party, and there were people, as I said, within the Portuguese colonies that also led armed struggles like Neto in Angola and Mondlane in Mozambique. And because he was an agronomist and poet, my suspicion is that a lot of Cabral's training was more in, quote unquote, regular radicals, it may still be socialists, but more regular, radical, liberal, social and political philosophy that was just part of modern discourse in Europe and then in Africa at that time.

PA: So you're resisting here specifically the label of a Marxist. So you're saying that he's swimming in the same socialist waters as everyone else, but he's not like a doctrinal Marxist.

Malam: No, there's no evidence of it. And when I've written about Cabral and Marxism, I've always been concerned about how, yes, he was reading Marx, he knew Marxism and so on and so forth, but there's no evidence that that was ever explicitly an acknowledged guide for his reflections. He did deploy Marxism, attacked Marxism on class and all that, yes.

PA: Yeah, maybe we can talk about that a bit, actually. So what he does with the idea of class. Do you want to say something about that? And then I'll turn it over to Femi and maybe expand on it.

Malam: He said that if you take class struggle to be the engine of social change, that by so doing you will have eliminated so many societies that didn't have, as the engine of history, who did not have classes. So that's where he looked at Africa and he said, well, you know, we may have something that looks like. And people forget that he wrote a seminal essay on the class structure of Guinea, where he eventually came to terms with what are those classes and where he introduced the idea of the class that is part of classic. So I think those are some of the things that make people think that, yes, he was part of that Marxist tradition. So what he did instead, which I think was the most creative part of all this, that many Marxists need to pay attention to was to say that classes may not be there, but you always have the mode of production. So if you want to explain how history evolves, look at how the mode of production evolves through time.

PA: So maybe to make that more concrete, the idea would be something like if you could have an agrarian society with no classes, right? So there's no working class and capitalist class, but there's still a mode of production, which is something like their use of their animals or something.

Malam: Exactly. And that would then give you an idea of what kinds of social relations are built upon those material structures and how those evolve over time will enable you to see that they may not have classes, but they're making history because they're producing.

PA: Femi, do you want to add anything to that?

Femi: Ultimately, I think I agree with Malam's characterization of it. It's certainly not the case that Amílcar Cabral conceived of himself as a doctrinaire Marxist. Whether we want to ascribe that label to him is a different question. And frankly, I don't even think that's the right way to read him, partly because of the thing Malam just said at the end there. I do think it's plausible to read him as doing some kind of reconstructed Marxism, because as we were saying before, it was in the air in terms of the anti-fascist movement in Portugal, which we do know that Cabral was an active part of. And they were familiar with that literature. But nowadays, as history has moved forward, Marxism and communism or socialism in some circles are almost synonymous. But of course, we know Marxism was one particular doctrine in a broader set of leftist doctrines, a broader set of radical doctrines, a broader set of materialist doctrines. I think what we can say clearly is that Cabral was a materialist. He didn't think that Marx had any kind of special hegemony on materialism. Marx was just one materialist thinker among other materialist thinkers. And I think that plays into what we were just talking about, about this class structure. Because this way of thinking about class, the insistence that all history hitherto is a history of class struggle. That's not just supposed to be a kind of claim about what the word history means, but that's actually supposed to be an empirical claim about what societies have actually been like. And just as Malam was saying, I think we can read Cabral as attempting to actually answer that question empirically. If we look at the history of the Bassari or the Fula or Mandinka or whoever, do we find the recognizable structures that maybe Marx or Marxists would expect to find? And he seemed to just answer empirically, no, there are some societies where we don't find those structures. And so this claim is just false. But he's still committed to materialism as a method and as a way of thinking. But Marx just provides one example of that.

PA: Okay, great. So I think that gives us a very nuanced sense now of how he's responding to socialism slash Marxism. There's one particular idea that he's known for, which revolves around this concept of class, which is the notion of class suicide. So this is specifically about one class within the soon to be revolutionary society, I guess. Can one of you try to have a go at explaining what class suicide means and why it's a necessary step in the liberatory struggle?

Malan: I think if I may just jump in here, the whole point for Cabral was that the colonial situation, and this is where the convergence with Fanon becomes very significant. The colonial situation is one where the colonizers try to peel off a small segment of the society that it turns into, quote unquote, allies in the colony, reward it in a way that will make it actually feel that it has something when it really does not have anything, and become then partners in crime with the colonizers against their own people. Okay. And Cabral, even though it was still close to the big change to independence in many African countries and all that, but over the course of the first decade of that period, it became very clear to him how some of those just stepped into the quarters vacated by the colonial authorities and kept things pretty much the same way. And to that extent, they were serving not the ordinary people, not the masses of the population, but themselves. People think that class suicide, at least in some renders that I'm familiar with, they meant that people just abandoned their class and then joined the other class in struggle and stuff like that. The problem that I find with that quite often is that those who say they commit class suicide and join that struggle then become some kind of aristocracy of labor within the labor movement, within those classes, or become a Leninist vanguard that continues to be the order givers. Whereas for me, Cabral's idea of class suicide is precisely a change not just of location and all that, but of orientation in terms of remaking class society in the way that begins to open up to the possibilities of greater equality among all, greater delivery of a life more abundant for the generality of the population. So to that extent, whatever privileges pertained to the offices that you are holding, you know, by that class division, the upper part of which you now occupy was there, will practically be liquidated, broken down.

PA: There's another well-known phrase in Cabral which is about that change in orientation. I'd like to ask Femi about this, which is the so-called re-Africanization of the mind. He also calls that a return to the source. And the idea here is that he's reorienting people who are kind of turning away from the colonialists' bureaucracy and committing themselves to the welfare of the people are supposed to be inspired somehow by the resources of traditional African culture, which I think is a really interesting idea. But it seems to stand in some tension with something else that we find in Cabral, which is that he's actually quite critical of at least some aspects of that culture because he basically sees it as superstitious. So Femi, do you think that that's a tension in his thought or even a contradiction in his thought?

Femi: I don't think it's a tension at all. So one of the ways that Cabral puts it in National Liberation Culture, which is an address he gave, he says that what people should aspire to do is return to the upward paths of their culture. Right? So he's not acknowledging or he's not failing to acknowledge that there are aspects of culture or tradition or we could use the word superstition. There are things that people believe that they believe on the basis of the development of history up till now that we should set aside or refine or revise. But doing that kind of critical work of your own history is different from just wholesale whole cloth assuming someone else's history. So all he's saying is have this critical perspective based on where you're from, not where other people are from. But that doesn't mean fail to be critical. It just means here's the use you should make of your critical faculties. Apply it to the history and development of the culture you are embedded in.

PA: Right. And that localism, again, to me seems to at least potentially stand in tension with something else we find in Cabral, which is this kind of universalist perspective that he takes. So maybe one label we could use for this is humanism. A quote that I picked out that I thought we might discuss is he says: “before being Africans, we are men, human beings who belong to the whole world”. And that makes it seem like the context, even if he's thinking about the traditional cultural roots of the place he lives, this universalist perspective might prevent us from thinking of him as a kind of localist or even a pan-Africanist, right, because he seems to be thinking here at the level of humanity as a whole. Do you think that's fair? Or do you think it's a problem in his thoughts?

Malam: No. I don't think there's any tension there at all for him. And this, again, where we need to go back to his education. Part of the problem that I have with a lot of the historiography of ideas in Africa is when people begin to talk about traditional society, begin to talk about pre-colonial Africa, begin to talk about tradition versus modernity. And what that does is to muddy the waters. Because for people like Cabral, like Nyerere, like Nkrumah, the whole lot of them, they were embracers of the modernity that colonialism pretended it was bringing to them, which, of course, I argued in a different work, that credit belonged to missionaries when it comes to English-speaking West Africa. No, there's no doubts about that. And they were all products of that. I call it the missionary school of modernity. So they did not say to their colonizers, you are different from us. Quite the contrary, they said, these ideas that you think you own, we would like to have them too. Okay? And as I tell everybody, hybridity is the very name of the survival of civilizations. So civilizations that are built on purity, they die out. They don't justify, they die out. So the point I'm making is that for Cabral, the idea that what the Portuguese were doing and other colonizers in other places, and the Portuguese were the worst in Africa because of their own backwardness to start with, violated something that was not just racial, that was not just demarcated by geography. It goes to the very heart of what it is to be human. And that's why he would then say to his cadres and so on and so forth, no, we don't kill just to kill. We kill because we have to. And we never forget that those that we are killing and those among them who are just injured who don't die deserve care from us if we can give it. Because when all is said and done, we are all instances of one type.

PA: Actually then there might even be a connection there to what Femi was saying about the so-called return to the source. Because just as you would take the best ideas from your own culture, you can also take the best ideas from European culture, and the reason they're the best ideas are just the ones that are valid for all humans. Right?

Femi: Yeah. That is, in answering your question, I referred to this upward paths way of phrasing it that Cabral said. And this is actually the exact point he was making in that paragraph. I'm just going to read it because I think it's helpful. He says: “people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from the oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture”. This is exactly, exactly the point that he's making. And he's making it at the level of theory here, but just as Malam was just saying, he was also making it in terms of the actual military actions of the party. There's a radio address that he gives in 1969 where he sends a message to the people of Portugal and talks about the moral standards for the treatment of prisoners of war from the fascist Portuguese military and talks about all of these things. And we can think of it as clever wartime propaganda, but I think he genuinely believes that this is what the materialist humanism he's built for himself points to as the right way to conduct this war, the right way to conduct political struggle. And his own political history speaks to this as well. It's not just an idea for him. He came up in the Portuguese anti-fascist movement and went from that to the Pan-Africanist liberation movement. It's not just theoretically or as a wartime propaganda machine that he believes in this common humanity, but it is a fundamental tenet of his politics.

PA: Well, Cabral did not live to see his struggle for independence succeed, but maybe we can think about what he might have done in the post-liberation period. So let's imagine a world in which he wasn't assassinated and he becomes the leader of the newly liberated Guinea and Cape Verde. So how do you think he would have pursued the task that faced people like Nkrumah also, so actually being political leader in a post-colonial setting?

Femi: My impression of Cabral is that he didn't see the distinction between theory and practice, I think, in the same way that some other thinkers might have. I don't think it's much of an accent that he was a soil scientist. I think he thought that the practical stuff of living was deeply political, not in the way that maybe these days we might politicize our interpersonal relationships, but I think in a more materialist-oriented way, the stuff that we do every day to keep ourselves here, to maintain solidarity with other people, to build and rebuild consciousness of our environment around us, are the basic things of politics. And so I imagine it would have looked from the outside to be a very technocratic regime. I think what would have been top of mind for Cabral after war would have been the condition of the soil, would have been the condition of the sewage systems, would have been the public health infrastructure. And part of the reason that I think that is because during the War of Liberation, they liberated territory from the Portuguese Empire and maintained de-facto political control over those sections of Guinea-Bissau. And guess what? Their focus was on literacy programs and their focus was on public health and maintaining party and community-controlled justice systems. There's a great book on the militant education of the PAIGC, that's his political party, by Sónia Vaz Borges, but she runs through all the stuff that they were doing to just organize life in the parts of Guinea-Bissau they had already functionally eliminated Portuguese imperial presence from. And I think that's where his focus would have been had he survived.

PA: Okay. Malam, do you want to add anything to that or say anything else about his legacy?

Malam: I'll go straight to the political and the economic. And I want us to pay very serious attention to what happened to the country that he left behind. It became two countries. One became a narco state. The other is now the only country in Africa that is a middle-income country under PAICV rule. And for me, that says something about if we are going to speculate, I don't think he will have fallen into the trap of a one-party state. No way. And that's again what I mean by going back to this modern tradition that they were all schooled in and how they understand the various freedoms that are part of the liberal, with a small L, project of modern philosophy. And Cape Verde continues to be a different place from the rest of the continent, both in terms of political succession and how they run their lives in terms of having no resources. All the resources are on the mainland. They are not in the islands, in the archipelago. And how they have managed to use that to build a middle-income country is something that other people may want to study. And I don't want to separate. And they never repudiated the Cabral legacy. Quite the contrary, it continued for a long time to be the beacon for what they were doing. So how they were able to use what many people would dismiss as neoliberal economics and all that stuff to move their society along while having a pluralist political system that is respectful of individual rights, I think is not a departure from the legacy of Cabral, it's actually, I think, a realization of it. And that's why for me, it would be nice to just oppose Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau.

Comments

Add new comment